Imagine you are an incredibly busy and stressed out graduate student (this shouldn’t be hard to do) and you have started to experience increased fatigue over the last three months. In addition, you sometimes feel odd heart palpitations and even shortness of breath when you are simply walking across campus to give your samples to a collaborator. You are carrying out experiments in the lab during regular work hours, and for some reason you just feel tired and exhausted all the time. To try to overcome these symptoms, you start integrating two daily 15-minute naps on the highest floors of the building where you work. Despite your practical efforts, these symptoms — fatigue, palpitations and shortness of breath — do not seem to disappear.

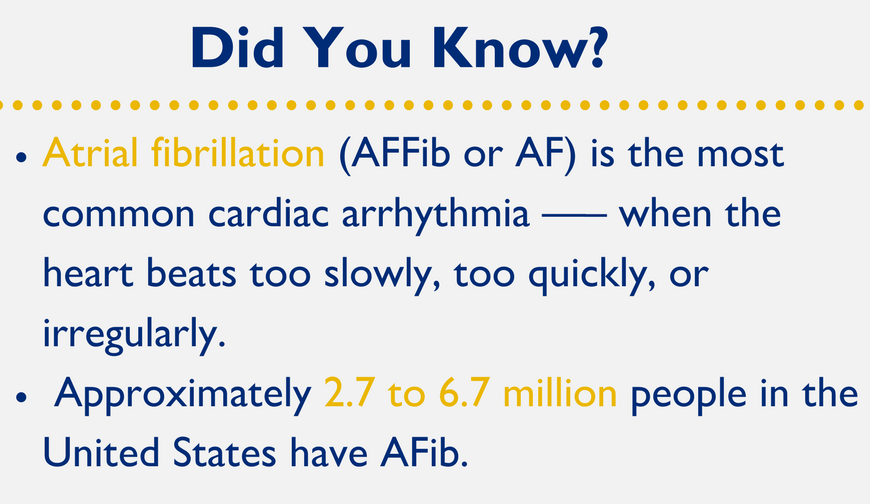

The fictitious (but relatable) graduate student described above suffered from atrial fibrillations. Atrial fibrillation (AFib or AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia — when the heart beats too slowly, too quickly or irregularly — and approximately 2.7 to 6.7 million people in the United States have AFib. Roughly 2 percent of people younger than 65 and nearly 9 percent of people 65 years or older suffer from AFib. Often, people who suffer from AFib don’t have evident symptoms and do not know they are affected until they go through a medical examination. Other affected individuals may experience irregular heartbeat, heart palpitations, lightheadedness, extreme fatigue, shortness of breath or chest pain. AFib can lead to blood clots, stroke, heart failure and other heart-related problems. When left , AFib doubles the risk of heart-related deaths and is linked to a five-fold increased risk for stroke.

What if there was a way to quickly measure your heart rhythm whenever you felt heart palpitations using just a watch? What if these heart rhythm measurements could be stored and sent to your doctor so that you can get back to your experiments without feeling guilty for not addressing your symptoms?

After two years of careful evaluation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), AliveCor announced on Nov. 30, 2017, that the KardiaBand is now available for purchase for $199 along with its premium service app ($99 annual fee) to be used with the Apple Watch. This rather expensive device, now FDA-cleared, can generate heart rhythm data that meets clinical quality requirements for accurate diagnosis of AFib. Clinical and nonclinical testing were performed to demonstrate that the device is substantially equivalent to an electrocardiogram (EKG), which measures a heart’s electrical activity and is the traditional method to check for signs of heart disease.

Unlike conventional EKGs, which are often performed in a doctor’s office, a clinic or a hospital room, and often after a life-threatening event, the KardiaBand is a personal EKG worn on the wrist. The EKG data can be sent directly to a cardiologist, who is able to see the patient’s daily EKG readings, as well as receive a notification when a particular result does not match previous ones, implying a potential change in that person’s heart rhythm. In an interview with CardioBrief, David Albert, cardiologist and AliveCor founder, said that “KardiaBand is often recommended to atrial fibrillation patients by their cardiologists to monitor their condition.” He also explained that, in other cases, it has been used to monitor people with palpitations, leading to a specific diagnosis, such as supraventricular tachycardia.

However, it is important to keep in mind that this device may not be the best option for every patient, since individuals with a more serious cardiac disease might benefit from other therapeutic interventions. Moreover, this device is not meant to replace professional medical care, but is instead intended to make it easier for patients and physicians to differentiate between normal heart rhythms and AFib.

In the future, medical technology advancements such as the KardiaBand will hopefully reduce fatalities from heart disease and stroke and improve the productivity of health care systems by reducing the economic burden of disease and the cost of care. Expectantly, device manufacturers will continue to make practical medical devices that doctors can use to keep up with their patients, including the busy and stressed out graduate students.