A few weeks ago, I completed my master’s degree in public health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Through the help of two projects I worked on during my master’s degree, I rediscovered a niche in the field of global health that I find particularly unique and exciting.

This niche is the field of international medical education. My interest in this field was first sparked during college, when I went on a medical relief trip to a remote part of Guatemala. I was fascinated by the disconnect I noticed between the education provided at medical schools in Guatemala and the traditional medicine practiced by many providers in the community. I spoke with a number of people who had received very different types of medical education in Guatemala, including formal biomedical training, midwife apprenticeship training and a knowledge of healing acquired through years of serving as the village’s curandera, a social leader who also fills the role of community healer.

I also spoke with a medical anthropologist who taught at one of the universities in Guatemala and had spent his career studying the varying types of training people receive in this country. He described the need to expose medical students to the different types of healing seen throughout the country, especially in remote indigenous communities, so that they would be adequately prepared to work with other providers and place their own knowledge in the context of the community’s health views and needs. Through this preliminary experience, I began to appreciate the art of crafting a medical education curriculum designed to prepare its students to care for patients in diverse environments.

When I started medical school four years ago, I became swept up in the hustle of studying and memorizing vast amounts of new medical knowledge. Toward the end of my second year at Hopkins, I connected with Steve Sozio, a nephrologist who is very involved in medical education both at Johns Hopkins and abroad. He began telling me about a medical education project he was designing and implementing in Istanbul, Turkey. I was immediately hooked.

This past fall, I was afforded the unique opportunity to travel to Istanbul with a group of doctors and students, including Dr. Sozio, to help teach a class at Bezmialem University and examine whether a research training module could be successfully implemented in a Turkish medical school. The curriculum we were teaching is called the Scholarly Concentrations curriculum, and it is a required class at Johns Hopkins for all first- and second-year medical students.

Through this experience, I recognized the challenges of adapting a portion of the curriculum from a U.S. medical school to fit the needs and goals of an institution in another country, particularly one with some different foundations and values underlying its medical education. For instance, research is an important component of medicine in the U.S., and this passion for academic inquiry extends through all levels of practice and training. In Turkey, medical school and residency admissions are nearly completely reliant on students’ national examination scores, and thus it can be more difficult to inspire students to pursue projects that might detract from their perceived preparation time for these examinations.

Thus, in Turkey, I experienced the challenges of international medical education through a very different lens compared with the one I experienced in college. Nevertheless, I still learned that it is important to work in this field with a comprehensive knowledge of the environmental nuances that impact how education must be structured.

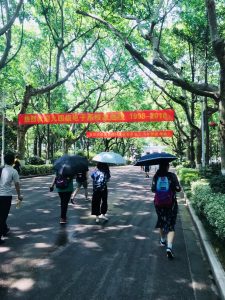

I recently returned from a trip to China, during which I was helping with a collaboration between Johns Hopkins and Drum Tower Hospital in Nanjing, China. The two institutions are working together to help establish an innovative residency program in China that will hopefully be the first ACGME-accredited training program in the country. I spoke with and observed a number of different teachers and trainees at Drum Tower Hospital to gain a broad sense of the specific nuances and challenges of developing a U.S.-style residency program in China.

Again, I observed the challenges of transposing a U.S. medical education system to another country and the need to adapt that system to the environment in a way that will give it the best chance of thriving. Research is highly valued in China, and medical students can start medical school with a clinical or research background — in essence, the equivalent of either our traditional premedical curriculum or a scientific master’s degree or Ph.D. Thus, students approach clinical training from a very different array of experiences, which makes it challenging to standardize education and adequately prepare everyone for independent clinical practice. This was an equally fascinating, yet very different nuance of the medical education system from what I had previously experienced in Turkey.

My experiences in Guatemala, Turkey and China have demonstrated the diverse challenges that make international medical education interesting. I am excited to continue exploring this field of academic medicine through a global health lens as I continue my own education.

Hi Rebecca. You've had some very interesting experiences. Is there a way to standardize a specific segment of global medical training which appeals to everyone and yet allows medical students to practice the methods of their country while implementing new techniques? To me, this is similar to crossing ethnic boundaries and cultures to benefit the people.

Comments are closed.