In the world of HIV, two fundamental equations define our understanding. The first is “undetectable = untransmissible,” meaning that when the viral load of person living with HIV becomes undetectable, they are unable to transmit the virus to others (untransmissible). U=U is the goal of treatment because, in the absence of a cure, treatment can allow people with HIV to live relatively normal lives. The second equation is “silence = death,” a stark reminder that in the absence of persistent and vocal advocacy for people living with HIV, lives have been lost in the past and will be lost in the future.

In the world of HIV, two fundamental equations define our understanding. The first is “undetectable = untransmissible,” meaning that when the viral load of person living with HIV becomes undetectable, they are unable to transmit the virus to others (untransmissible). U=U is the goal of treatment because, in the absence of a cure, treatment can allow people with HIV to live relatively normal lives. The second equation is “silence = death,” a stark reminder that in the absence of persistent and vocal advocacy for people living with HIV, lives have been lost in the past and will be lost in the future.

Since the start of the global HIV epidemic in the 1980s, science and advocacy have been inextricably linked. In 1981, hundreds of young homosexual men began dying from rare diseases such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumonia. Over the course of the year, it became clear that a new epidemic was unfolding — people were getting sick from blood transfusions, women were contracting this disease through heterosexual sex, and children were born sick to sick and dying parents. In 1982, the disease was officially named acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A year later, Dr. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and her colleagues identified the responsible retrovirus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Still, it took 10 more years and more than 100,000 deaths for the advancement of highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), which finally curved the death toll from AIDS.

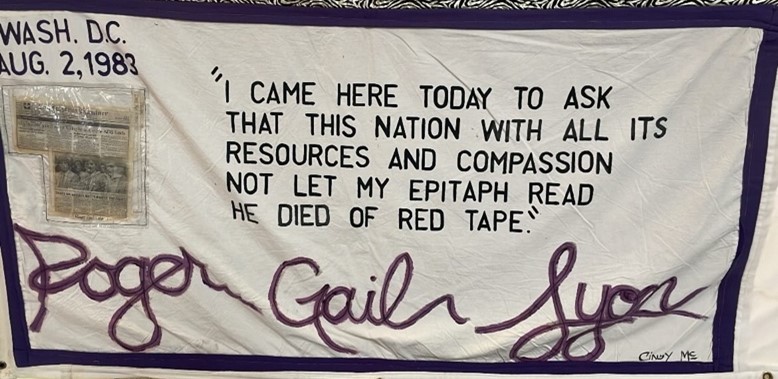

During this time, activism played a critical role in driving health reform and scientific progress. In 1987, Larry Kramer founded ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in New York City with the goal of pressuring governments, public health agencies and the pharmaceutical industry to act. TIME later called ACT UP “the most effective health activist group in history” for its efforts to push for better treatments, faster drug approvals and improved clinical trials. Through direct action protests, such as the 1988 sit-in at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), ACT UP fought for lifesaving investigational drugs and expanded clinical trials to include more women and people of color. The group’s advocacy was instrumental in speeding up the FDA’s approval process and securing key policies such as the Ryan White CARE Act of 1990, which provided crucial funding for national HIV care. Ultimately, activism was essential not only for advancing science, but also for ensuring a more equitable and effective response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

As I entered the conference hall of the 32nd annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2025) in San Francisco, I immediately felt the deep connection between HIV research, care and activism. The first thing I noticed were pieces of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, colorful but dark reminders of a time not long ago when an HIV diagnosis was a death sentence, not a chronic illness. During that time, entire friend groups and communities could be lost in a matter of months.

Later that day, we listened to a moving lecture from Rebecca Denison, the founder of the Women Organized to Respond to Life-Threatening Diseases (WORLD), the first AIDS advocacy group focused on women. Rebecca, who has lived with HIV for 40 years, shared her powerful personal journey and the stigma she faced when she was first diagnosed. Her words reminded us of how deeply San Francisco was affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis and the pivotal role the city played in advocacy. She also encouraged us to attend the ACT UP protest scheduled for the next day in front of the conference center.

“Research is resistance.” “Science is survival.”

These were some of the phrases echoed at the ACT UP protest, which provided a venue for around 100 scientists, doctors and community members to stand defiantly in the face of unprecedented challenges. As a young scientist attending the conference, I was reminded that thousands of activists across the country were needed to enact change, and it is my generation’s turn to step up.

Today, there are 40 million people living with HIV around the world, with 30 million of those on ART. The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) stands as the largest global provider of HIV prevention — including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and ART — delivering life-saving treatment to millions around the world. Alongside PEPFAR, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has played a critical role in supporting global HIV/AIDS programs, providing funding for prevention, care and treatment services in many countries heavily affected by the epidemic. However, both PEPFAR and USAID’s HIV/AIDS programs are at risk of losing vital funding due to recent executive orders and shifting political priorities, threatening access to treatment for countless individuals in need. For those who are aware of the early years of the epidemic, the fear is palpable: if we do not act now, we risk losing many lives, just as we did in those early, tragic years. The loss of funding could dismantle vital infrastructure and further marginalize communities already facing the brunt of the global HIV/AIDS crisis, undermining decades of progress. In light of this, the ongoing activism for HIV/AIDS treatment and care remains as crucial as ever.

“Everyone has the right not just to live, but to science.”

“Silence means death. Science saves lives. And the silence is too loud.”

As the conference came to a close, one message resonated above all: the fight against HIV is far from over. The progress made through decades of research, activism and community engagement is now at risk, and history warns us of the consequences of inaction. But just as those before us refused to accept silence, we too must continue to speak out, demand access to treatment, defend the right to science and ensure that no one is left behind.

“Act up! Fight Back!”

To fight back, please find information on how to contact your congress members here: refugeesinternational.org/actions/tell-your-member-of-congress-save-usaid-save-lives.

Related Content

- From Baltimore to Guatemala: Experiences in Global Health

- Global Threats to Public Health: Dr. Peter Hotez on Climate Change, Conflicts, Poverty and Antiscience

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.