One of my responsibilities as a graduate student in the history of medicine is to serve as a teaching assistant to Johns Hopkins undergraduates who elect to take the department’s courses. Traditionally, the history of medicine survey course has mostly attracted premedical students who are looking to satisfy the school’s writing requirements with content that feels relevant to them. That is, they are coming more for the medicine, and less for the history.

Most of our students look to the biomedical system with awe, and hope to one day be inducted as full-blown members of this small community that has a special power to make authoritative pronouncements about the human body. They are undaunted by the ways in which this power is waning, such as through widespread anti-vaccine sentiment, political attacks on research institutions, or the internet’s explosion of easily available (though sometimes dubious) health information. In the face of such assaults to medical authority and increasing mistrust from outside the profession, these students remain true believers.

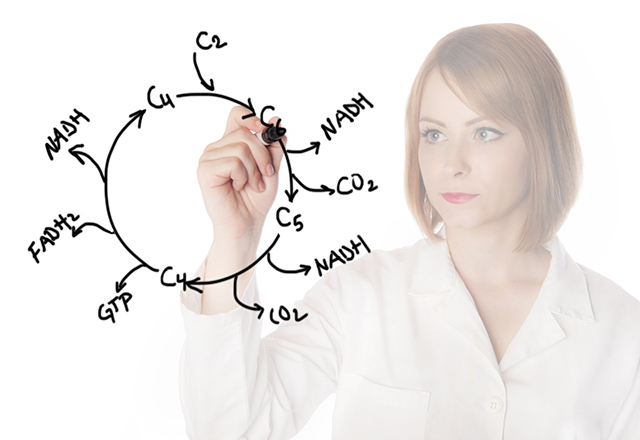

I share many of their beliefs, and yet as I stand before them, I also seek to unsettle some of their core assumptions. When sitting in a biology class and memorizing the Krebs Cycle, or later in a medical school lecture learning about the types of renal tubular acidosis, it is easy to imagine that these details, and the myriad others one is expected to commit to memory, are objective truths. Never disputed, only neatly established through the scientific method, they exist in a reality far apart from the messiness of our social universe, where fallible humans stumble through life making countless mistakes. But as historians of medicine, it is our job to reanimate medical “truths” (whether still considered valid or disproven) with all the rich context that brought them into being.

My own work focuses on the history of eugenics, which in the not-so-distant past, was embraced by the medical mainstream. What we now regard as a shameful episode in medical history was supported by countless scientific research papers, powered by the most rigorous statistical methods at the time (in fact, many of our most widely used statistical tools, including the chi squared test, standard deviation and correlation coefficients were developed by eugenicists). And although the word “eugenics” is taboo in mainstream discourse, the ideas it represents remain hotly debated, from the ethics of “designer babies” and gene editing to Sydney Sweeney’s latest advertising campaign with American Eagle, where she boasted of good genes/jeans.

I believe that teaching this history is a critical component of medical training, even among the vast majority of doctors who do not plan to pursue any graduate studies in the humanities. It serves as a stark reminder that behind the official-looking data sets and algorithms lie imperfect, biased, fallible humans — descriptors that apply even to the best intentioned among us. History has the power to imbue medical trainees with the humility and skepticism necessary to question medical dogmas, many of which are destined to be unsettled sometime in the future. By empowering students to never stop asking questions, we can shape a generation of doctors who will better serve their patients by recognizing and dislodging harmful ideas, before such theories are relegated to the historical articles they read in my class.

Related Content

- Digitizing Diagnosis: A new book by fourth-year medical student Andrew Lea

- Summer Reading from the Hopkins History of Medicine Department

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.