Imagine going to the doctor to be tested for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. You will likely have to travel a long distance to get to a clinic, and, once you arrive, your blood will be drawn and sent to a central testing laboratory for analysis. You will then have to wait for the results to be delivered to the clinic and return to the clinic for your diagnosis. In Zambia, it takes approximately 92 days for this process to be completed. When you are an HIV-positive mother waiting to find out if your newborn child needs antiretroviral therapy, each of those 92 days can mean the difference between life and death for your baby.

Management of infectious diseases such as HIV in sub-Saharan Africa has been a major part of the career of William Moss, M.D., a professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He works closely with the Johns Hopkins research field site in Macha, Zambia, to study the epidemiology behind infectious diseases that devastate Africa.

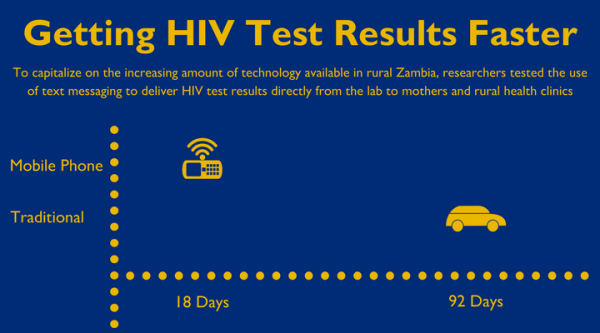

New work from Moss and his group focuses on finding ways to shorten the 92-day wait for HIV test results. Capitalizing on the increasing amount of technology available in rural Zambia, Moss and colleagues conducted a study using text messaging to deliver HIV test results directly from the central testing lab to mothers or rural health clinics. The results, published in the April issue of BMC Pediatrics, found that by sending a text message directly to the mother, they could reduce the time from sample collection to receipt of diagnosis to just 18 days.

Unfortunately, the use of mobile phones is still not widespread; only 30 percent of mothers in the study had ever used one. Luckily, the local clinics do have mobile phones, so delivering results via text can still decrease the time to diagnosis, to approximately 36 days. By cutting 56 days off the wait for diagnosis, HIV-positive children can receive antiretroviral therapy nearly two months earlier. Reducing the time to treatment significantly ameliorates the clinical symptoms of HIV infection and prevents the progression to AIDS, vastly improving their quality of live and longevity.

As noted by Moss, implementation of the mobile phone messaging system for test result delivery was by no means trivial. It required the hiring and training of new staff as well as the purchase of mobile phones and “talk time” for the phones. Other major obstacles for mobile phone messaging systems include unreliable network coverage throughout rural areas, lack of digital literacy and skills, and the large gender gap: Men are much more likely to have mobile phones, while women are responsible for the children’s health. Additionally, villagers were often skeptical of the benefits of using a mobile phone when they had relied on their traditional system for years. However, with the right funding and infrastructure, the utilization of technology throughout Africa has the power to have significant and widespread impacts on health care. Studies such as this highlight the great potential of available technology to encourage governments and private investors to take note and get involved. Someday soon, nationwide mobile phone messaging systems may become common place, drastically cutting the time to diagnosis and improving each individual’s access to care and treatment.

Related Content

More amazing things that mobile phones are doing for public health:

- Small Study Affirms Accuracy of Free Mobile App That Screens for Liver Disease in Newborns

- Getting Enough Sleep? Johns Hopkins Mobile App Helps Physicians Identify Common Sleep Disorders in Patients

- Mobile App Could Help with Heart Attack Recovery

- mADAP | A Mobile App for Adolescent Depression Awareness

- Anatomy App Offers Interactive Learning from Johns Hopkins Expert