“From Prison Cell to Ph.D.” is a series following the journey of Dr. Stanley Andrisse, who was convicted of 2 felony drug charges and sentenced to 10 years in Missouri prison. He is now a postdoctoral scientist in pediatric endocrinology and trainee leader at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“This is a collect call from the Northeast Correctional Center,” says the operator, as I am thinking to myself how much I hate her voice. I am semi-anxiously waiting for my brother to pick up on the other end. The parole board had recently told me I had only six months left and I couldn’t wait to share the good news.

“Stan, what’s up. Yo, it’s not good, lil bro. It’s not good,” my brother started immediately upon answering the line. He quickly followed with “the infection spread to his brain. Pops is in a coma.” Everything he said after that was just a distant mumble. My mind was transcending into that hospital room with my father, outside of these prison walls. The pain rang deep through my bones. Holding back the tears that were just moments away from flowing like a river, I went back and locked myself in my prison cell — my cage. My mind was whirling. I could not cry now. Crying is weakness. By now, I had seen things that I never imagined I’d see in my life. I did not cry then. I could not cry now. Instead, I would take hold of my pain and transform it into purpose. It was shortly after this call that I decided to apply to graduate school.

Applying from a Prison Cell

Applying from a Prison Cell

The application process was an uphill battle from the very start. The prison rejected all of the college information packets I had requested. They didn’t meet mail guidelines. With the help of friends on the outside, I eventually developed a system around this roadblock. It took me roughly four months to string together six applications, all in Missouri because I was not allowed to leave the state. I was so proud and hopeful. The rejection letters, however, only took a few days to start pouring in. Rejection after rejection after rejection.

As of today, I’ve visited over 20 student organizations in the last 20 days. No, I’m not running for executive board president. My student council days are over. I’ve spent the last few weeks meeting with student government groups from universities all over Maryland to garner support and spread awareness about the Maryland Fair Access to Education Act of 2017, colloquially called Ban the Box on College Applications. The bill passed with bipartisan support but was vetoed by Governor Hogan and will be up for override in January 2018.

A recent story in the New York Times, From Prison to PhD, has received an outpouring of attention. Michelle Jones, a formerly incarcerated person, was considered this year’s top candidate and was accepted into Harvard’s History Ph.D. program, but the offer was rescinded by the university president because of political pressure implying, “it would look bad for the university.” Subsequently, several endowed chairs and professors wrote an opinion piece stating, “We are Educators, Not Prosecutors,” demanding that the university alter its non-discrimination policies.

A Roadblock to Education

Many colleges and universities claim to push toward having a diverse and inclusive student body. However, one piece of diversity seems to always find its way out of this conversation of inclusiveness. One single sentence hampers this idea of obtaining a full representation of the spectrum of society. How many of you recall your college application process? I imagine that you likely don’t remember the box asking about past criminal convictions. But for many people like me and Michelle Jones that little box is a mountainous barrier to future success.

By requiring applicants to disclose their criminal history, universities impose a barrier to education. This process reduces the applicant to the mere moment (often decades ago) when they incurred a criminal record rather than seeing the full person with all their interests, skills and experiences.

By requiring applicants to disclose their criminal history, universities impose a barrier to education. This process reduces the applicant to the mere moment (often decades ago) when they incurred a criminal record rather than seeing the full person with all their interests, skills and experiences.

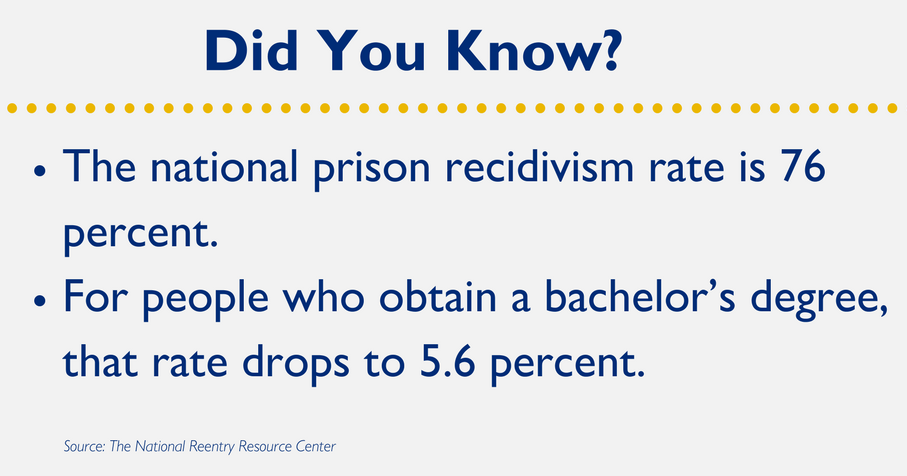

Johns Hopkins University, like many other universities throughout the state and the nation, ask that applicants respond to the box. Studies show that leaving a check mark stating “yes, I have been involved in the criminal justice system” greatly lowers your chances of a follow-up to your application. President Obama and the Department of Education support removing the box. The history of this policy is NOT rooted in empirical data. Schools that do not have the box are equally as safe as those that do. Most of the crimes on campus are by first-time offenders with no criminal history. The national rate of people returning to prison (recidivism) is 76 percent. For people who obtain a bachelor’s degree, that rate drops to 5.6 percent. It’s a no-brainer. Statistics support college after incarceration. The box is NOT a public safety tactic.

The box denies people a chance to follow a trajectory that takes them away from their previous circumstances. College administrators are not trained criminal justice professionals. Groupings of crimes/violations have vastly dissimilar meanings in different states. Moreover, this policy disproportionately affects applicants of color, due to mass incarceration primarily affecting people of color. The box is discouraging to many applicants. Sixty percent of people who checked “yes” did not complete the application.

Education is transformative to the person and to the community. Education lowers poverty and progresses public safety. Competing in today’s economy is more and more difficult without a college degree. Everyone wishes to increase their opportunities and be gainfully employed upon graduation. That same opportunity should not be deprived to persons who have already paid their debt. We must open our institutional doors, not create barriers.

Demand that universities/colleges in Maryland provide an application that does not ask applicants any question(s) pertaining to past guilt or conviction of a misdemeanor, felony or other prior offense in the initial application process.

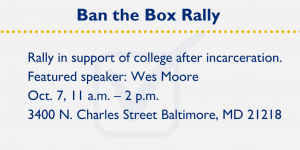

My nonprofit, in partnership with several other community organizations, is organizing a rally in support of college after incarceration. Wes Moore will be the featured speaker. The rally is Oct. 7, 11 a.m. – 2 p.m. at the JHU Beach (3400 N. Charles St). Please sign the Ban the Box on College Applications petition and visit the Facebook event or the website for more details.

Studies on college after incarceration

- https://csgjusticecenter.org/nrrc/facts-and-trends/

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/changing_minds.pdf

- http://www.communityalternatives.org/pdf/passport/Benefits-of-Higher-Ed.pdf

- http://www.communityalternatives.org/pdf/Reconsidered-criminal-hist-recs-in-college-admissions.pdf

- https://www2.ed.gov/documents/beyond-the-box/guidance.pdf

- http://fromprisoncellstophd.org/ban-the-box