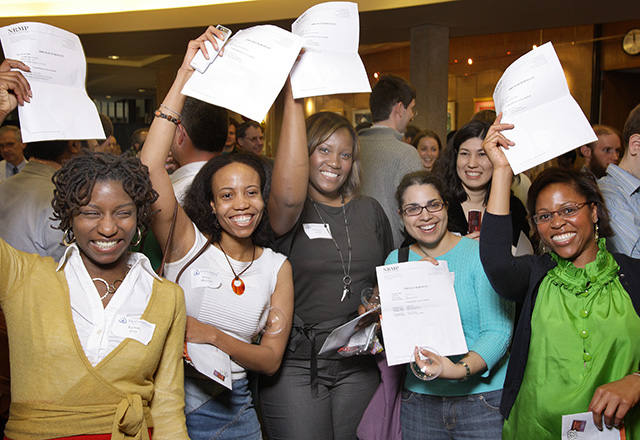

Every March, thousands of fourth year medical students simultaneously open letters containing the names of their future residency programs. A pediatrics resident nearing the end of her training reflects on things she wishes someone had told her as she prepared to become an intern.

- Most days, you will have to choose between getting enough sleep, food and exercise.

At some point, your eating habits will devolve. Your hormones will fluctuate. You will sacrifice sleep on 24-hour calls and regain it on weekends off. You’ll try and likely fail at making a serious commitment to exercise.

That being said, I slept eight hours every day that I wasn’t on call. I gained the night shift weight. Then I lost it by meeting my Fitbit goals and rejecting workroom leftovers (so many carbs!). I spent my one night off per week preparing for my next seven shifts.

You won’t get what you want all of the time. Keep your priorities straight, and you will get what you need most of the time.

- Burnout affects nearly every resident, and no two residents are affected in the same way.

Classic physician burnout looks a lot like depression: disengagement, more work-related errors, less empathy for patients. However, no two physicians experience burnout in the same way. Some of my co-residents claim they were their best work selves during their most burned out periods — then they went home, and they didn’t have the emotional reserve to engage with loved ones. Look for burnout everywhere so you can anticipate and intervene before your professional (and personal) life is negatively impacted

- You will learn to work in a feedback vacuum for much of your residency.

In medical school, the feedback is (a little too) constant. Once you get to residency, that feedback frequency drops off significantly. At times, you’ll feel like you’re operating in a vacuum. Ask for constructive and specific feedback from everyone — your staff members, students, fellows and attendings.

- The logistics of running a hospital or clinic will make you question why you chose to be a physician.

Your job as a resident is to learn how to be a doctor and to run the hospital or clinic. Although the priority should be on the former, sometimes the latter dominates. No one signs up for medicine for the paperwork. When the logistics of the job feel overwhelming, brainstorm how to offload less educational tasks. Can a discharge coordinator help navigate home care orders? Can a bedside nurse help review medications? Pool your resources, then delegate kindly and effectively.

- Be selfish about your learning.

At this stage in your training, everyone assumes that adult learning theory principles apply to you. Therefore, it will be up to you to get the educational experience you need out of residency. Once you recognize your weaknesses, address them! Sign up for the elective that explores a perceived deficiency. Stretch your clinical comfort zone by working in a remote or underserved area. Now is the time to ask all the questions and make all the mistakes, while your liability is minimal and your support is maximal.

- The best physicians learn to embrace uncertainty.

I once read that the only true ignorance is certainty and conviction. A commitment to medicine is a commitment to lifelong learning, and all learning curves bring uncertainty. Once logistics and basic medical decisions become more comfortable, uncertainty manifests as “the art of medicine”: when to operate, how long to medicate, whether to palliate. This form of uncertainty endures forever. The first family to ask me to be their children’s primary care provider told me it was because I was honest, especially when I didn’t know the answer. Learn how to manage uncertainty gracefully. Your ability to acknowledge uncertainty while still maintaining authority will make or break your patients’ trust in you for the rest of your career.

- Communication saves lives.

As a brand new intern, I was really worried about learning “the medicine.” Then a respected mentor told me that anyone can learn “the medicine,” but not everyone will become an effective physician. Now it’s clear to me that compassionate and careful communication is what elevates a physician from average to exceptional. Learn to read the signs from people — from a hesitant family, a worried nurse — and respond to them. Give others a window into your thought process. At the end of residency, there will be patients who haunt you and patients who make you feel like you did something worthwhile. The goal is to have as few regrets as possible — and that starts and ends with effective communication.

- Support your co-residents and staff members, who may become more like family than friends.

I routinely cover shifts for co-residents, compliment my team members in front of my patients, and respond quickly to concerns. As a result, I’ve been able to get uninterrupted hours of sleep on call, go home early from slow shifts, and obtain coverage for important personal events. I’ve also seen residents help with each other’s child care and family emergencies. It’s not always convenient, but being a team player contributes to a culture of support and sharing that is essential for a positive residency experience.

- Training is a marathon, not a sprint. Pace yourself.

Intern year is intense, eye-opening, and career defining. It’s easy to think that you just have to get through the next week, the next rotation, the next year and it’ll get better. Don’t fall into this trap — in reality, there’s always that next thing. Learn to be present for the journey and you’ll be much less likely to burn out at any point in your career.

- Be flexible in pursuit of your wellness goals.

It’s easy to get frustrated about no longer having time for the things you used to enjoy. Be kind to yourself. I miss being able to do hours of studio yoga multiple times per week, but now I walk to work and save the yoga for weekends off. You’ll probably have to be a spectator rather than a participant in a lot of beloved activities during intern year. However, whenever you think it will never get better, remember: Second year is coming.

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.

Such wonderful advice! As a corollary to #5, housestaff should be proactive about seeking regular and ad hoc chats with faculty. We're here because we care about education - so knock on doors! You don't need to be prepared in any particular way, but you should intentionally follow up on action items immediately (to summarize) and later (to update).

Comments are closed.