The explosion of digital health interventions has prompted significant investment. As the industry has begun to mature, substantial effort has been made to create an efficient, two-sided market — with startups on one side as sources of innovation, and enterprises on the other as drivers of large-scale impact. To get a sense of current trends and who the big players are, I attended the inaugural Rock Health Enterprise Insights Series in Washington, D.C., this spring. In addition to addressing where the industry is heading, the event highlighted how Washington policymakers, industry leaders and startups are working together to create regulations that protect consumers while encouraging innovation. Here I share insights from the event, in an effort to help bring the discussion to fellow trainees and health care professionals interested in applying technology-based solutions to health care.

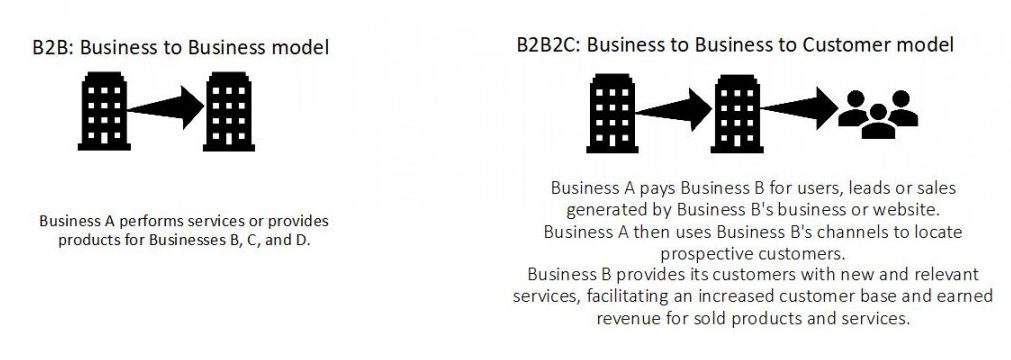

The digital health care industry is moving from a direct business-to-consumer (B2C) to a business-to-business (B2B) model.

Digital health care covers a wide range of services, including clinical decision support systems, electronic medical record systems, telehealth, wearable devices and mobile health. As can be expected, certain services lend themselves better to B2B models over others. However, according to Rock Health data, 85% of business models are enterprise-focused: either B2B or B2B2C (business-to-business-to-consumer, see the illustration). What does that mean for a fledgling medical startup? Though selling to payers, providers, biopharmaceutical companies and other large businesses is challenging, it is something that should always be on the radar as a potential business model. For example, one success story discussed at the event was that of Omada, a digital health diabetes program that partnered with Cigna, an insurance company that agreed to offer Omada’s services to all of its regional and national employer customers. This allowed Omada to scale up rapidly, helped Cigna expand its preventive care services, and gave patients a seamless user experience between the myCigna app and Omada’s diabetes program. Importantly, the event also emphasized that the #1 acquirers of digital health startups are other digital health companies — suggesting that a feasible strategy for a small startup might be to 1) become acquired by a larger digital health care company, 2) leverage the larger company’s resources to negotiate a better B2B partnership with insurance companies or large employers.

There is an app for everything — but is that a good thing?

One point that the event reinforced was the sheer volume of health apps — it seems like everyone is trying to build a similar solution for a slightly different problem. Unfortunately, patients have multiple comorbidities. Are we building a system that expects patients to have an app for every disease?

Not only is that not feasible, it could potentially dilute engagement across the board due to app fatigue. At the same time, one company expanding its solution across multiple diseases might not be the appropriate solution either. This fails to capitalize on the strengths of each digital health intervention — for example, Omada has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with diabetes, while QuitMedKit is well regarded in the smoking cessation app sphere. It makes sense for leaders in their space to work together, like components of a multipart, well-oiled machine. However, most smartphone apps and wearables are siloed from one another. Addressing this will be an important next step in moving digital health care to broader clinical practice.

What about reimbursement?

A big question that often comes up in the world of digital health care is reimbursement — how will we pay for these new services? On a basic level, one key takeaway was that there is a Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) benefit category that could be used to cover physician interpretation of the digital health tool — the same category that currently covers physician interpretation of services such as Holter monitoring. In order for a digital health care service to be covered, requirements would need to be met. The event encouraged early engagement with CMS in formats such as premeetings to discuss options.

Finally, for me, the biggest reimbursement question has been related to telemedicine — the delivery of diagnostic, consultative or therapeutic health care services using electronic communication technologies. One attendee, the chief medical officer of a large hospital system, shared that a key to the successful integration of telemedicine in his organization was its capitated insurance system. Since his physicians were salaried, it was in the best interests of his health system, physicians and patients for a percentage of a doctor’s urgent care shifts to be telemedicine. Physicians and patients benefited from the increased convenience, and the health system benefited from lower costs. However, in a country with so many insurance companies and payment models, to me this suggests a potential future with differential adoption of digital health technologies, and it raises the question of how this might affect health care disparities and access to care.

Ultimately, attending this event created just as many questions as it answered, and I came away with a much deeper understanding of some of the remaining challenges to tackle. Although the event’s focus was mobile health, I hope that similar opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration will expand to include stakeholders in other aspects of digital health care, including leaders of electronic medical record services, developers of clinical decision support systems and companies involved with health data sharing.

Related content

- Top Five Strategies to Generate Great Ideas and Build a Successful Startup

- How Business School Is Making Me a Better Doctor

- The State of Digital Health

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.