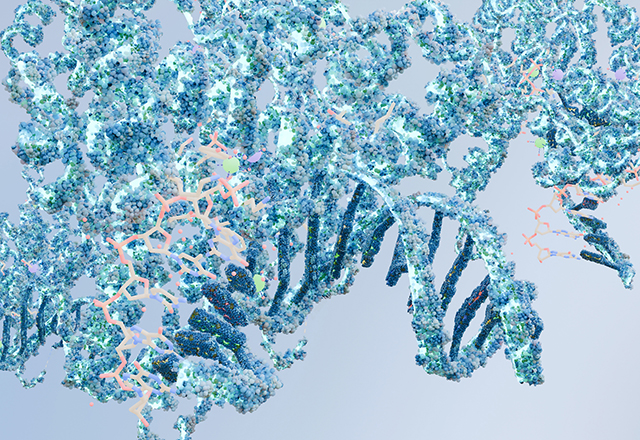

Smoking causes cancer. That may be enough for some people, but for those interested in what happens in between, what follows is one explanation. Upon inhalation of tobacco smoke, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and certain nitrosamines are deposited in body tissue. These are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and other enzymes, forming reactive metabolic intermediates that form aberrant bonds with DNA strands. Bonds that go unaltered by repair mechanisms can induce permanent mutations. After a thousand or so inhalations, an arbitrarily large number of metabolite-DNA bonds, and a further countless permanent mutations, perhaps one occurs in a gene responsible for tumor suppression. Crippling of this gene, alongside others, destabilizes cellular growth and eventually, a mass of squamous cells begin to jut out of the bronchus. All this to circle back to the original point: Smoking causes cancer.

It probably doesn’t come as a surprise when I say that I knew this before coming to medical school – not all the stuff about nitrosamines or mutations, but the abbreviated idea that smoke is bad for breathing. I’ve heard the phrase enough from my parents who, wagging their fingers, warned of chilling consequences far more immediate than carcinogens if they ever caught me with a cigarette. Now, in medical school, where I am encouraged to learn why action A causes illness B, the thought of a TP53 mutation is its own formidable deterrent.

A molecular understanding of how cancer arises instills some amount of certainty in the cause-and-effect relationship. Yet knowing that cancer can originate from an acquired gene mutation doesn’t explain why people keep smoking, or why some communities are more burdened than others. For example, one could be born genetically predisposed to nicotine addiction. Others might share a household with smokers or reside in communities that are more aggressively targeted by tobacco advertising. Beyond the molecular perspective (of which there are many), lies another world of complex pathways that extend into public health and sociology. Sorting out these perspectives is difficult if not impossible, which leaves some frustration when I think of how, sometime in the future, a patient might ask me why they are ill. A long-winded discussion of aromatic hydrocarbons or tumor suppression genes would not cross my mind as a potential answer. I am left with the question: Which explanation would be most appropriate? Or which one will I be most responsible for?

It seems clear, at least, that a proper explanation will have to involve something beyond a phrase as deceptively simple as “smoking causes cancer.” After all, research into smoking-induced cancer did not end when Dr. Doll and Dr. Hill published their epidemiological study into tobacco smoke as a cancer risk factor in the 50s. It was, in fact, after their study, that concerted efforts from various and diverse disciplines readily contributed to the growing characterization of tobacco smoke in its molecular and sociological interactions with community health. It occurs to me that this diversity in understanding is an important aspect of explaining illness as a physician, and that a pluralistic view is the only one that captures that whole picture of epidemiology, chemistry, sociology, and grief. It also occurs to me that taking in and understanding this massive, multipronged view might just be the easy part. What follows is the challenge of explaining to a patient why they are ill, with as many explanations as they need, and through every pathway I hope I have taken care to learn.

Related Content

- Teaching Cancer Cells to Self-Sabotage

- What Birds in Love Teach Us About How the Brain Processes Competing Motivations

- Cancer and the Mutation Paradox

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.