This blog post is part of an in depth look at research linking sleep and Alzheimers.

Think about your sleep quality for the past few months. Has your sleep been routinely interrupted or has it been restful? Has your sleep become worse with age? Perhaps the stresses of your daily life have intruded upon your ability to sleep well, or perhaps you have been trading sleep for more work or play.

The quality of our sleep diminishes with age and can be disrupted for many different reasons. Working hours are constantly on the rise, making certain jobs one of the many culprits of sleep restriction in Western societies. For example, intensive care unit health care professionals are often required to work at night, causing them to stretch their capacity to be awake and compromise their nightly sleep, thus becoming sleep-deprived and more likely to make mistakes.

Sleep, a most fundamental need in life, is a universal activity in all mammals but also one of the least understood aspects of all beings. The way you feel while awake depends in part on what occurs while you are sleeping. The health consequences of sleep deficiency can occur in an instant (such as a car crash due to drowsy driving), or they can accumulate over time. Mounting scientific evidence is suggesting that sleep problems and poor-quality sleep may raise the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

What is sleep and why is it so important?

When you are awake, you are in a state of consciousness supplemented by sharp perception, realistic thinking, awareness of your surroundings and physical activity. In contrast, sleep is a behavioral state characterized by decreased perception, relatively low responsiveness to the environment, and physical inactivity (or rest). Although a resting body is the most noticeable feature of being asleep, the brain remains active at varying levels, during which it controls sleep and completes vital tasks, such as strengthening memories.

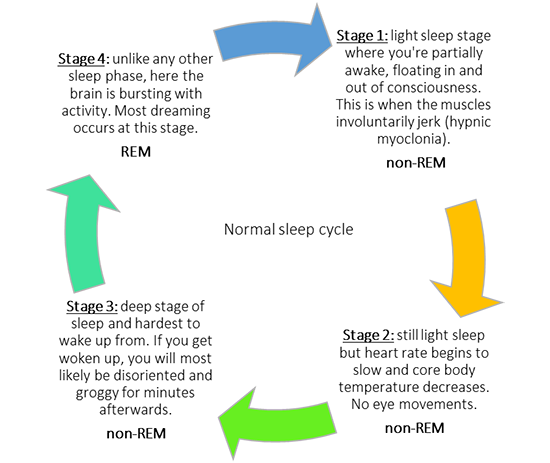

The two major sleep states are REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM (or slow wave sleep). When you fall asleep, your body “cycles” between different stages of both REM and non-REM sleep. For instance, over the course of the night, your body will go through stages of REM/non-REM four to six times, spending an average of 90 minutes in each stage, unless you are sleep-deprived.

“It is thought that the different stages of sleep have different emotional, cognitive and physical functions,” said Yo-El Ju, assistant professor of neurology and sleep medicine specialist at the Hope Center of Washington University. “For example, REM sleep is when most people dream and where the brain processes emotional context in a safe way. In contrast, the non-REM sleep seems to be important for the downscaling or “pruning” of synaptic connections (connections between brain cells).”

As you go about your day, you are forming new memories and new synaptic connections. Letting your mind rest by sleeping affords your brain a period to downscale or “prune” those new connections so that only the strongest and best ones remain.

“For most mammals, sleep is essential for life. If you deprive animals of sleep for very long, they die. We don’t understand why,” said David Holtzman, head of the Department of Neurology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “We don’t know exactly what is critical during sleep for brain functions such as memory, but there is evidence of synaptic plasticity (the ability to strengthen or weaken brain connections over time) being augmented by sleep.”

Another newly discovered event that occurs during sleep is the activation of a housekeeping routine called the glymphatic system, which is a clearing system that takes away waste products surrounding the brain cells. Although this housekeeping support system is somewhat active during the day, Maiken Nedergaard at the University of Rochester and his team discovered that it is during sleep that this neural cleansing work kicks into high gear, making sleep a key period where debris left over from a busy brain activity day is cleaned away, like taking out the trash at the end of each day.

Related Content