Should science be political?

Trick question — science is inherently political because the vast majority of science is funded through the federal government. So, if you don’t relish the idea of competing against your peers for an increasingly shrinking pool of grant money, it’s important to care about the process by which money is federally allocated.

On that note, in March a group of Ph.D. candidates and I got a chance to learn about the federal process for funding science at the Association for the Advancement of Science’s Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering workshop in Washington, D.C. Throughout the workshop, we got an invaluable inside look at this complex system from an array of people involved in science policy, including current and past Ph.D. scientists, congressional legislators and staffers, and policy employees from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF).

On that note, in March a group of Ph.D. candidates and I got a chance to learn about the federal process for funding science at the Association for the Advancement of Science’s Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering workshop in Washington, D.C. Throughout the workshop, we got an invaluable inside look at this complex system from an array of people involved in science policy, including current and past Ph.D. scientists, congressional legislators and staffers, and policy employees from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF).

Despite my preconceptions that science support and funding were tanking, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that funding has fared relatively well, and that support for science is strongly bipartisan (except for the issue of climate change). As is usually the case, my misconceptions stemmed from my ignorance of the process.

So, how does it work?

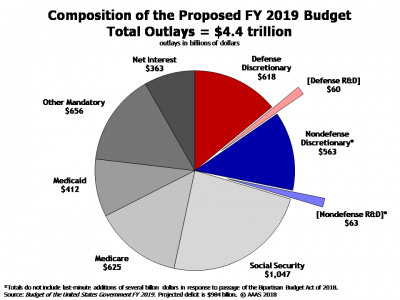

The answer, with egregious brevity: All science funding is allocated as part of the entire federal budget (think the same funding that covers Social Security, Medicaid and the military). First, the executive branch of the government (aka the president and their crew) makes recommendations for the next federal budget with input from federal agencies (such as the NIH, NSF and Department of Defense). However, these recommendations are not binding, and Congress is free to abide by or completely ignore them. Next, the legislative branch (the Senate and the House of Representatives) decides on its own dollar amount for a yearly budget, and then congressional appropriations committees determine who gets what (for example, the Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies Subcommittee has to divvy up its allotted amount of money between agencies such as the FBI, NSF and NASA). Then, the Senate and the House, which each have their own budget requests, must agree on a spending bill for the next fiscal year. Then the public dollars allocated for research and development (R&D) are funneled out to the agencies like the NIH and NSF.

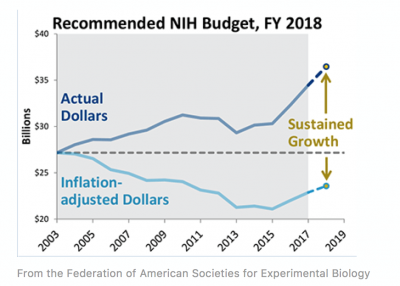

The good news for scientists is that most legislators are supporters of R&D and, despite concerns about an increasing deficit, they have been happy to funnel money toward science in order to make up for funding “losses” due to inflation. With this in mind, the NIH budget has enjoyed several years of multibillion-dollar funding boosts.

The good news for scientists is that most legislators are supporters of R&D and, despite concerns about an increasing deficit, they have been happy to funnel money toward science in order to make up for funding “losses” due to inflation. With this in mind, the NIH budget has enjoyed several years of multibillion-dollar funding boosts.

That being said, we need to continue to care about this trend so that more grants can be supported by federal agencies. Luckily for us at Johns Hopkins, advocating for science is easy. I had the fantastic opportunity of meeting with congressional staffers for multiple Maryland legislators on Capitol Hill to talk about my research and the importance of sustained funding for R&D.

If science funding, or any other science policy issue, is important to you and you’d like to meet with a policymaker, all it takes is a quick email to the Hopkins Government Affairs office to obtain your best point of contact. Then, simply email that person to schedule a meeting. Legislators and staffers love to meet with students and hear firsthand about what the dollars they’re fighting to procure for science are doing.

So what were my takeaways from the CASE workshop experience?

- Science is definitely political, as it is largely funded by the government.

- Science is widely supported by both political parties.

- Advocating for science is important and feasible.