Photos courtesy of the author.

Guest blogger, Emily Rodriguez, is a second-year medical student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

When I decided to attend Johns Hopkins, I knew that I was walking into an institution that embodied the saying “the world is your oyster.” As a first-year medical student, I coupled that with the personal motto “you are limited only by your imagination.” At Grand Rounds, invited speakers, who once stood in my shoes as medical student trainees, reminded me that at Hopkins, nothing is impossible.

As a first-year medical student, we are encouraged to pursue a scholarly project in one of five categories: clinical research, basic science, public health, HEART (Humanism, Ethics, Education, and the Arts of Medicine), or the History of Medicine. At an institution where every faculty member has an open-door policy to join research, I knew that I would always have the opportunity to do clinical, public health or even basic science research. Coming to Hopkins, my goal was to be a sponge and take advantage of as many unique opportunities as possible. After learning that Hopkins was home to the first ever Department of the History of Medicine, I acknowledged that I may never again have the time to sit in an archive and conduct a rigorous historical analysis.

After deciding to pursue a history project, I was a bit lost — I had many interests, and it was hard to narrow them down to just one. I want to pursue a competitive surgical specialty, so I knew that if I was going to take a summer to do a history project, it had to be novel. I also knew I wanted to do a project that would allow me to immerse myself in a Spanish-speaking country, since I hadn’t traveled abroad before. Desires and interests aligned when I learned about a new archival source that was uncovered in Guatemala. My adviser succinctly stated that “there isn’t anything much more novel than analyzing a source that experts haven’t even fully processed yet!”

With some background knowledge and interest in authoritarianism in Latin America and the role of medicine within military conflicts, I decided my analysis would focus on the role of the hospital system in the Guatemalan military regime.

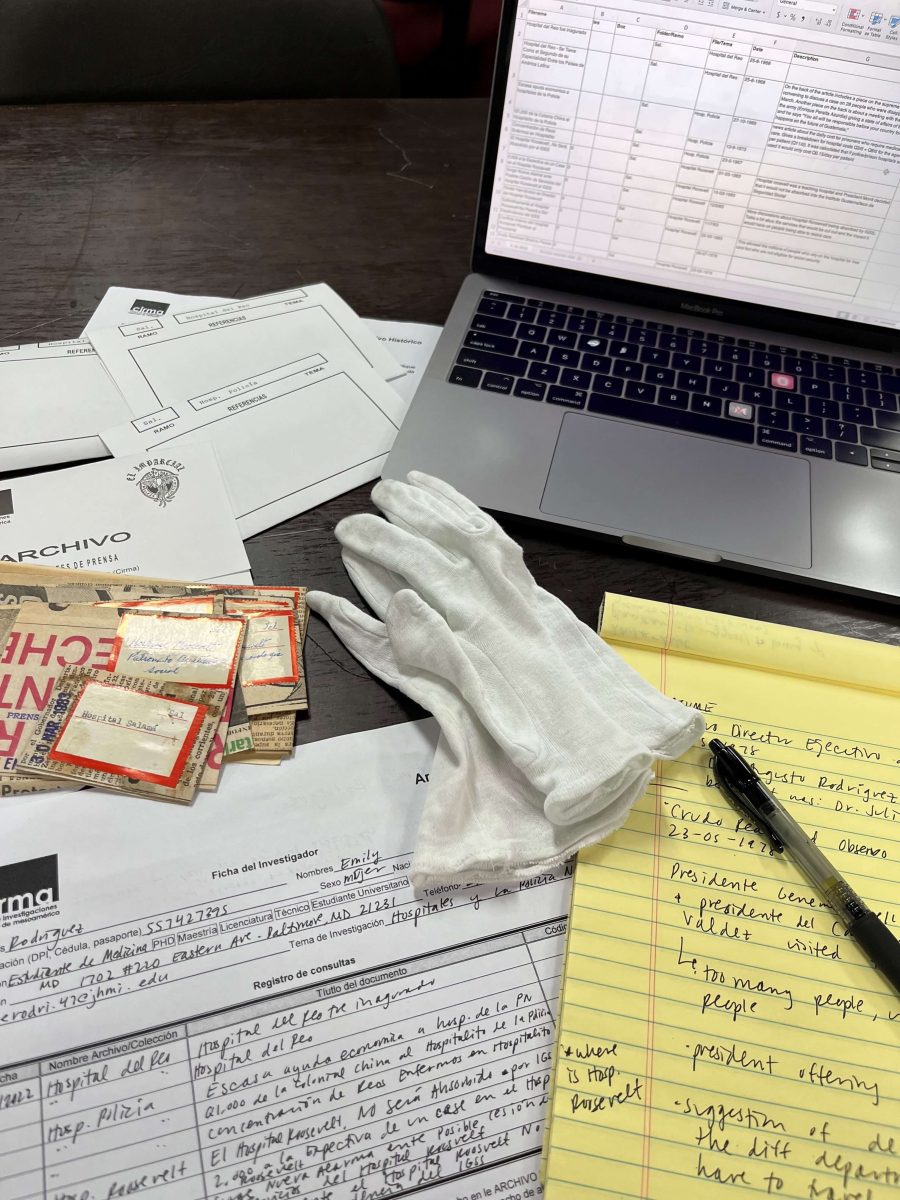

I began emailing and meeting with history of medicine in military regimes experts across the country, who guided my secondary literature search and taught me how to do archival analysis. Archival research consists of reading primary source documents — newspapers, letters, unpublished works and intercepted communications — organizing them by themes and dates, and then using them to construct a narrative. I identified my two main archival sources — Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA) and the Historical Archives of the Guatemalan National Police, both located in Guatemala. I traveled to the country in July 2022, where I spent 1.5 weeks in Antigua, Guatemala, and 1.5 weeks in the capital, Guatemala City. Serendipitously, I was there during the inaugural celebration of the blessing of Antigua, which consisted of a weeklong celebration of the history of the city and country. The festivals and parades allowed me to fully immerse myself within the community while learning about and researching the historical events that have shaped the country as it is today.

At CIRMA, I sorted through nearly 2,000 newspaper clippings and articles from the 1960s to the 1990s, focusing on building the political and social context of my topic. Due to stringent policies to access the in-person archives, my next phase of research was confined to the digitized portion of the National Police Archives. Without labels or search refinement capabilities, I clicked through hundreds of folders and files, reading police intake forms, secret correspondence and confidential documents. Often, I ended my long days without reading a single document for use in analysis. Resiliency was rewarded, however, and I uncovered many documents supporting my hypotheses. Once I began to accumulate data, I weaved together the contextual history, the evidence in the documents, and my secondary literature to craft a historical picture of the way in which the hospital system was situated in the military regime in Guatemala.

Not only did my scholarly concentration research allow me to travel to a new country to learn about a critical piece of history that has ramifications for the practice of medicine in any country, but I was also able to share that work at the Medical Student Research Symposium and will be presenting at the American Osler Society Annual Meeting this May.

Related Content

- School of Medicine Hosts LMSA – Northeast 50th Annual Regional Conference

- Med Student Creates Animated Documentary for Scholarly Concentration Project

- Digitizing Diagnosis: A new book by fourth-year medical student Andrew Lea

- The Hidden Joys of Medical School

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.