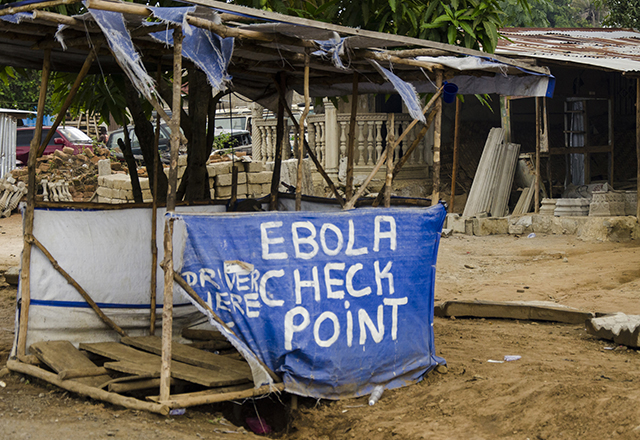

Though it may seem distant now, 2014 was a tumultuous year for the global health community. One of the worst Ebola epidemics in history was ravishing communities in West Africa, spreading to health care workers, sparking superstitions among locals and demonstrating how devastating a single virus can be on the world stage. Many likely remember the widespread panic that accompanied the epidemic and the attempts to synthesize a vaccine in time to treat patients. Daring, cutting edge research was performed, eventually resulting in vaccine trials in the most acutely affected areas. Most importantly, this epidemic showed us the importance of a concerted effort between multiple countries and organizations to treat affected patients, prevent spread of disease and educate the public.

Lessons Learned from Previous Ebola Epidemics

Ebola, of course, has not gone away quietly. We have had 10 outbreaks this year alone, mostly in Western and Central Africa. Ebola virus is the etiologic agent of Ebola virus disease (EVD), and despite its small size (only 11 genes!), it is one of the most infamous viruses of our time. First discovered in the 1970s, Ebola virus has sporadically emerged throughout the decades, but was mostly localized and easily contained. The mode of transmission is still unclear, but it is believed to be spread via bodily fluids. The reservoir (the natural non-human host which usually carries the virus throughout the year, but can initiate outbreaks when the right circumstances bring humans into contact with this host) is suspected to be bats or bush meat. The largest epidemic to date was from 2014 to 2015, during which more than 11,000 people died from the disease. The causes of this epidemic are numerous, but were likely exacerbated by the initial obstacles of limited laboratory testing and slow global health organizational responses. Countless doctors and health care workers risked their lives to contain the disease and treat those infected. Though the epidemic was eventually stopped in 2015, with a coordinated effort by many countries including the United States, there are many lasting effects of the disease. EVD survivors are sometimes alienated from their communities, and health care workers often have difficulties returning to their home after an outbreak. Fortunately, vaccines were rapidly developed and tested in African communities as soon as possible, and these have been critical in responses to outbreaks since then.

Three years later, we are still battling Ebola. The remarkable difference is in how new outbreaks are being addressed. One of the more recent was declared officially over on July 24, 2018, after a coordinated effort by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In this epidemic, the government was forthright in reporting new cases, and the WHO was rapid in their response. Sadly, 33 people died from EVD during the two-month span of the epidemic, reminding us of the deadly potential of Ebola virus. This epidemic even reached an urban center where millions were at risk, Mbandaka, which normally adds fuel to the fire of an epidemic. Yet the WHO provided emergency funds within hours of the outbreak, a vast difference from the response in 2014. In addition, new vaccines were available due to careful research and development in the private and public sector. All in all, the coordinated management of this particular outbreak was a success story. But rather than pat the Democratic Republic of Congo on the back, and give WHO a round of applause, we should now look at exactly what went right, and how we can apply this to other emerging infectious diseases in the future. Organizations in global health security, such as the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (CHS), aim to do just that.

Three years later, we are still battling Ebola. The remarkable difference is in how new outbreaks are being addressed. One of the more recent was declared officially over on July 24, 2018, after a coordinated effort by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In this epidemic, the government was forthright in reporting new cases, and the WHO was rapid in their response. Sadly, 33 people died from EVD during the two-month span of the epidemic, reminding us of the deadly potential of Ebola virus. This epidemic even reached an urban center where millions were at risk, Mbandaka, which normally adds fuel to the fire of an epidemic. Yet the WHO provided emergency funds within hours of the outbreak, a vast difference from the response in 2014. In addition, new vaccines were available due to careful research and development in the private and public sector. All in all, the coordinated management of this particular outbreak was a success story. But rather than pat the Democratic Republic of Congo on the back, and give WHO a round of applause, we should now look at exactly what went right, and how we can apply this to other emerging infectious diseases in the future. Organizations in global health security, such as the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (CHS), aim to do just that.

Simulating Emerging Infections to Improve Preparedness

The CHS has a central mission of protecting health and strengthening infrastructure of communities around the world to prevent global health tragedies such as the Ebola outbreak of 2014. Seeking to improve Americans’ understanding of just how important global health security is, including engagement with the WHO and foreign countries, the CHS recently had a meeting with policymakers and health security experts in which they were asked to combat a simulated pandemic. Called Clade X, the emerging infectious disease simulated in this meeting was the result of years of work at the center. The fictitious virus was not extremely fatal or infectious, but spread person-to-person by coughing. The goal, director Tom Ingelsby explained, was for the scenario to be realistic. In this simulation, only two major cities were affected initially, though U.S. troops had been exposed, and no treatment or vaccine existed for the novel virus. Given the world’s experience with viruses like Ebola, one might hope that this exercise would be a piece of cake. But, Ingelsby warned, they “didn’t want it to have Disney ending. [They] wanted to have a plausible scenario.”

It resembled more of a Grimm’s fairy tale ending.

Within 20 months, a vaccine was not developed, and approximately 150 million people had died. Thankfully this was only a simulation, but these kinds of discussions are absolutely essential for policy and health experts all over the world. With world travel at our fingertips, and urban centers as hot spots for epidemics, it is all too easy for an infectious agent to spread in the absence of appropriate and swift involvement of international and national health organizations. This exercise emphasized the immense unknown threat of infectious diseases, whether natural or synthesized in a lab. The CHS identified key goals for the global health community — including bolstering global health security systems and working toward more rapid vaccine development — as critical to helping avoid a catastrophic outbreak such as Clade X. This hearkens back to the reasons for success in ending the Ebola outbreak in the DRC — concerted efforts and rapid vaccination were key in ending the spread of the disease. This Clade X exercise also revealed how important communication is, and emphasized that both policymakers and the media must be vigilant against misinformation and convey how policies are intended to benefit individuals’ health. Though the global health community has made progress in addressing epidemics, such as the 2018 Ebola epidemics, there is still much improvement to be made. These exercises are meant to prepare us for situations like Ebola, so that we can rapidly respond and contain health threats.

While Ebola epidemics are ongoing today, the progress in the international community’s response should give us hope. With centers such as CHS, and global health engagement by our government and others, we can work with policy and health experts to protect the health of people all over the world.