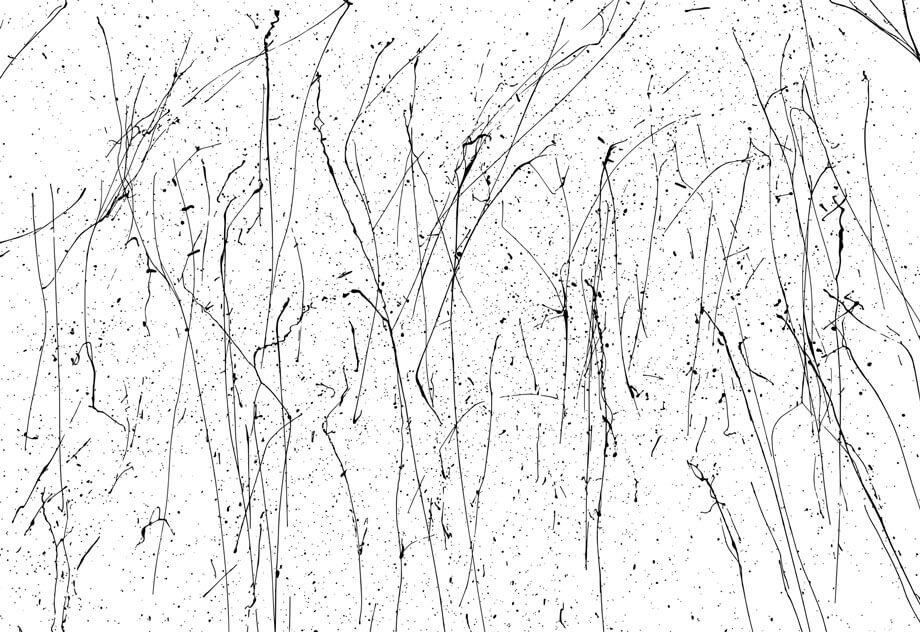

When peering at the spindly fiber of a nerve cell under a microscope, it’s easy to wonder what invisible cues might guide such a long protrusion as it grows toward its destination. To identify and isolate such a substance for the first time, however, required bravery and keen insight. This was the quest of the incredible neuroscientist Rita Levi-Montalcini, and she was certainly no stranger to bravery.

A bold beginning

Born in Turin, Italy, in 1909, Levi-Montalcini had to convince her father to allow her to enroll in a university and pursue a professional career, which he protested would interfere with her prescribed fate as wife and mother. She made up yearslong gaps in coursework in eight months before entering medical school at University of Turin. It was there, under the guidance of famous neurohistologist Giuseppe Levi, that Levi-Montalcini learned silver staining, a technique that would allow her to visualize neurons in exquisite detail. Then, in 1938, Benito Mussolini promulgated laws that banned Jewish people from academic and professional careers, forcing Levi-Montalcini from her university. This oppressive treatment did not keep her from scientific pursuits, however. As war loomed, she set up a makeshift laboratory in the bedroom of her family home.

Levi-Montalcini was determined to follow up on a finding by embryologist Viktor Hamburger of Washington University in St. Louis, who showed that removing the developing limb of a chick embryo led to reduction of the spinal neurons destined to innervate the appendage, which he attributed to a lack of some factor that promotes nerve cell development. Using silver staining to take a closer look, Levi-Montalcini drew a different conclusion. She saw that even with no limb bud present, spinal neurons proliferated and began to elongate, but then withered and died, implying that the developing limb supplies a factor that stimulates nerve growth.

The search for the factor

Having read her papers, after World War II, Hamburger invited Levi-Montalcini to visit his lab to expand her findings. There, graduate student Elmer Brueker found that a mouse sarcoma tumor could also attract nerve fibers in great abundance when transplanted onto a chick embryo. Acting on her intuition that this tumor tissue was releasing the same factor as the developing limb bud, Levi-Montalcini set up a brilliant experiment. She implanted the tumor outside the sac surrounding the developing chick — a separate area that nevertheless shares the embryo’s blood supply. The chick’s nerves sprouted wildly, demonstrating that a diffusible substance emanating from the tumor promotes nerve growth. These provocative findings led her to develop a more efficient assay to assess tissue extract growth-promoting activity — quantifying neurite outgrowth in cultures of isolated chick spinal neurons. The system enabled Levi-Montalcini and her colleague, biochemist Stanley Cohen, to finally isolate nerve growth factor (NGF), leading to its eventual structure determination by protein sequencing. The pair shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1986.

A lasting legacy

The implications of this work are wide ranging. Eyedrop medication containing NGF is effective in treating some eye diseases and is being studied for others. At the time of NGF’s discovery, the existence of diffusible growth factors was controversial, but to date, hundreds more such proteins are known to exist. Their roles in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases and their applicability as therapies are being investigated.

Levi-Montalcini’s contributions have never been limited to the sphere of scientific research, however. At the end of World War II, she risked her life to work as a medical doctor at a camp for war refugees, where infectious diseases were widespread. The first Nobel laureate to live to age 100, she was no less trailblazing in her later years, and continued to lead research projects, mentor young scientists and work at an educational foundation she started for African women and children. Having been appointed an Italian senator for life, she was a fierce advocate for scientific research, and once forced the reversal of a decision to withdraw government research funds by withholding her deciding vote.

Scientists often look to historic discoveries for inspiration. The story of Rita Levi-Montalcini shows us that in doing so, we should not only understand the scientific insights that underlie our research but also appreciate their intricate human context. Levi-Montalcini drew on her resilience, ingenuity and bravery to resist an oppressive regime and a patriarchal society. Her work should remind us that to reveal the finer details of biological processes, we may need to challenge societal forces when they pose a threat to the peace, safety and justice required for the unfettered pursuit of knowledge.

References

Abbott, A. “Neuroscience: One Hundred Years of Rita.” Nature. 458, 564–567 (2009).

Levi-Montalcini, R., Knight, R.A., Nicotera, P. et al. “Rita’s 102!!” Molecular Neurobiology. 43, 77–79 (2011).

“Rita Levi-Montalcini — Biographical.” NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2022. nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1986/levi-montalcini/biographical

“Stanley Cohen — Biographical.” NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2022. nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1986/cohen/biographical

Related Content

- Organoids — frustrating and full of promise

- Women in Biotech: Lessons Learned from the Johns Hopkins Science Writers’ Boot Camp

- Rethinking the Doctoral Qualifying Exam

- Reading and Writing the Immune System

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.