“From Prison Cell to Ph.D.” is a series following the journey of Dr. Stanley Andrisse, who was convicted of 2 felony drug charges and sentenced to 10 years in Missouri prison. He is now a postdoctoral scientist in pediatric endocrinology and trainee leader at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

I once waited at the polls for three long hours while a nice little old lady called every public official in the state of Missouri to try and help this excited young man vote in the Obama 2012 election. I knew I was a “convicted felon,” and I knew I could not vote. But, like many other things in my life, I thought, Hey, what does it hurt to give it a try? Twenty-plus calls later, an answer came direct from the governor’s office: This nice old white lady, who was pushing 90 years old easily, pulled me to the side and whispered to me, “The governor’s office says you have a criminal conviction.” I looked at her in disbelief. To my surprise, she gave me the same look of disbelief and said, “You ain’t committing any crimes right now,” she said. “They should let you vote.” She apologized. We shook our heads and parted ways.

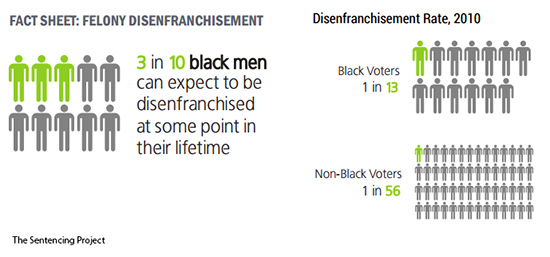

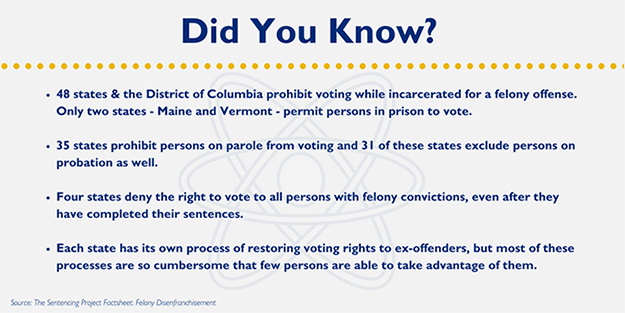

My home state of Missouri does not allow people convicted of a crime to vote until three years after the end of their supervision. For nearly 17 years, they took away my constitutional right as a U.S. citizen to vote for the people who will run our country. Why, might you ask? Because of felony disenfranchisement. In Florida, people with convictions will never vote again. Of the black population in Florida, 25 percent cannot vote. It is estimated that soon it will be 40 percent. Mass incarceration as a continuation of slavery is explored in the documentary 13th, titled after the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery.

This rejection brings me right back to my prison cell. Although I am free, I continue to have shackles on me. I am trusted to make scientific contributions that advance the well-being of our society, but that same society does not want me to vote. I am brought back to the euphoric agony of the 2008 historic Obama-McCain presidential election. I was incarcerated at the time, staring through a tiny 4-inch by 6-inch window on my prison cell door at a small TV in the common area, my cellmate looking through the top window, and me looking through the bottom. This closeness definitely violated the unspoken personal-space prison code of ethics, but this night was an exception. We were witnessing the election of the first black U.S. president. In prison, we had a designated lights-out time. But on this night, the guards also made an exception and left the TV on all night so that we could follow the election.

This rejection brings me right back to my prison cell. Although I am free, I continue to have shackles on me. I am trusted to make scientific contributions that advance the well-being of our society, but that same society does not want me to vote. I am brought back to the euphoric agony of the 2008 historic Obama-McCain presidential election. I was incarcerated at the time, staring through a tiny 4-inch by 6-inch window on my prison cell door at a small TV in the common area, my cellmate looking through the top window, and me looking through the bottom. This closeness definitely violated the unspoken personal-space prison code of ethics, but this night was an exception. We were witnessing the election of the first black U.S. president. In prison, we had a designated lights-out time. But on this night, the guards also made an exception and left the TV on all night so that we could follow the election.

A typical prison housing unit has one guard monitoring station, four wings, 25 cells per wing, and two inmates per cell, so roughly 200 inmates per housing unit. As a result of mass incarceration, about 25 bunk beds per wing were placed outside of cells, so there were 400 inmates in my housing unit that night, and about 90 percent were black. I will never forget how loud it was. People were banging on the doors in excitement and singing the new song by Young Jeezy, “My President Is Black,” in unison, hopeful that change was coming. It was a euphoric experience, but in the back of my mind, the agony of thinking that I’d never be able to vote was painful.

Fast forward to 2014, midterms: I’m now a biomedical scientist living in Baltimore. I walk right into the polls, not entirely sure what will happen next. They check my ID, hand me a ballot, and say good luck. For a long time, I simply thought that I would never be able to vote again. I was unaware of the differing laws by state and unaware of the power of unified voices to help change policies. Luckily for me, that same year Maryland started allowing people with felony convictions on parole to vote.

Last November, I walked into the voting poll location with a sense of happiness and pride. While others complained about the long and slow lines, I patiently walked along, while inside my head I was dancing like a kid awaiting a Christmas present. The euphoria was not an excitement about the presidential candidate selection (Hillary Clinton versus Donald Trump), but a sense of joy. I have been of the legal age to vote since the early 2000s. Yet this is the first presidential election that I have been able to vote in.

When I tell my noncriminal-justice-minded friends about how I could not vote for all those years, they are appalled. Most have no idea about this collateral consequence of conviction.

Related Content

- From Prison Cell to Ph.D: Spreading Hope to Those Deemed Hopeless

- The 2016 Election: Making Our Voices Heard in a New America

- Where the Presidential Nominees Stand on Science and Technology

Dr. Andrisse wondering if you were able to do any studying while in prison or was everything postponed until you got out? While your post is about voting as I'm a librarian I am very interested to know if you had access to a library and/or books while in prison and if so, if these were helpful to you in pursuing your educational dreams.

BTW I'm a patient at JH and have nothing but positives to say about the institution. Your story reaffirms that I'm at a good place.