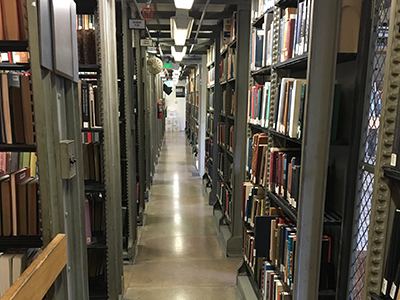

Above: Kristin's carrel at Welch Library

Mid-November 2018: I sit in my carrel watching the snow fall outside, a café au lait cupped in my hands and my elbows resting on the wooden barrier that protects me from falling eight floors to the bottom of the library. Historian Julie Livingstone’s book on debility and the African moral imagination lies open on my desk in front of a row of books on 19th-century Britain and the British Empire, ranging in topic from Victorian urbanity to 20th-century measles epidemics. The only light comes from the book stacks beyond the carrel’s caged door, probably as old as the early 20th-century building itself. I am the only person in the carrels this morning, and the only sound comes from the soft Christmas music streaming from my computer’s speakers.

What do I mean by a “carrel,” though? When most people hear the word, they think of a desk with wooden barriers, attached one after another. Yet as the picture of my carrel shows, older library carrels were built to isolate the individual for quieter work than even the library can allow. The Welch Library, built in 1928, has carrels on the top three floors of its stacks, which are also part of the Institute for the History of Medicine. Most of the sixth and seventh floor carrels are closed for repairs, though anyone can use them when they’re functional. However, the eighth floor carrels are explicitly for the history of medicine students. In their first semester, these students are assigned a carrel by the institute’s librarians. The students receive a tiny key to a padlock that gives them their own space in a library otherwise devoid of study space.

To many students, these carrels are too dark, too enclosed, too cold. Yet I am partial to the old library and its caged spaces with the large windows looking out over the Basic Sciences courtyard. Sitting in my carrel, I feel like a true academic, squirreled away in a quiet corner of the earth where the Wi-Fi sometimes works but often drops. It’s where I go when my living room or a coffee shop is too comfortable a place in which to work. For someone with horrible anxiety, the library’s cool, calm atmosphere clears my mind and enables me to read and write and read some more.

Because that’s what being a historian of medicine entails. You read until your brain hurts with the weight of experimental bodies and racist and gendered medical imperatives, and then you write about them until your conscience screams for help. A bright, cozy coffee shop just seems too cheerful a place in which to read about cows strapped to tables and vaccinated with experimental cowpox.

Of course, the institute and the Welch Library are more than their caged carrels. Their stacks alone are full of strange bits of history. For instance, while looking for literature for a project on menstruation last year, I stumbled across a 1960s pamphlet called Stonehenge: The Sex Machine (I had to laugh in surprise). Sometimes I roam the infectious disease section just to see what I can find. Sometimes I go down to the rare book room to delicately examine 19th-century books on smallpox vaccination. But I always return to my carrel to unpack my findings in silence. It’s a home in a medical archive, an opportunity many historians desire and few have. I may not have a fancy, well-lit office looking out over the Inner Harbor, but I have a place to write about troubling topics and to struggle through authors like Georges Canguilhem and Peter Galison. It’s a place to compose conference papers, grant proposals and lesson plans. And of course, it’s a place to gaze happily at the snow falling in the middle of a dark semester.