Since the U.S. Congress ratified the first federal health care plan under the presidency of John Adams in 1798,1 generations of legislators and medical professionals have burned the midnight oil to shape the U.S. health care system into an apparatus that delivers groundbreaking biomedical research and world-class clinical practice. Nevertheless, the modern U.S. health care system remains rife with inefficiencies that jeopardize the health and well-being of every American. One such inefficiency stands out as being particularly contentious among both federal governing bodies (FDA, HHS, CDC) and voters in the upcoming 2020 U.S. presidential election15: the rising cost of drugs. Surprisingly, the solutions that resolve a private sector issue may ultimately come from the private sector itself. A handful of creative business leaders have reoriented the behavior of legacy pharmaceutical companies or have spawned new companies, with the aim of solving the drug pricing dilemma through innovative business models that shift industry trends in favor of more affordable health care. Before exploring each of their proposed solutions, it’s worth examining the socioeconomic tradeoffs of drug development, as well as the reasons why drug prices have climbed throughout the years.

The Socioeconomic Tradeoffs of Delivering Life-Changing Products

Gordon Moore, co-founder of the Intel Corporation, coined the term “Moore’s Law” to describe the exponential rate with which computer processors were miniaturized from the 1970s to 1995.2 His observation that, “the number of transistors incorporated into a chip doubles every two years” encapsulated the single most important driving force behind the proliferation of powerful, portable and affordable personal computers. The drug development industry lies in stark contrast to the exponential gains in productivity enjoyed by the semiconductor industry. Drug discovery costs have doubled every nine years since 1950, an exponential decline in productivity that bears the unfortunate palindromic moniker of “Eroom’s Law”.3

Why has the productivity of pharmaceutical research and development regressed instead of progressed? Existing drugs in specific therapeutic areas, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, are so effective that new drugs require more costly clinical trials with larger patient populations in order to garner the statistical power to prove superiority. The FDA began to institute requirements that pharmaceutical companies perform large panels of preclinical studies that flag concerning side effects before drugs are allowed to be given to patients in clinical trials. While escalation of preclinical safety requirements is well founded, it has also driven the adoption of costly human resource departments to ensure compliance. Widely used reductionist approaches to screening compounds are effective at successfully identifying molecules that modulate the activity of a specific target protein. But these efforts often fail to reap a clinical benefit in the more complex setting of human disease.

These are among the many factors that hamper the productivity of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry. In terms of operational productivity, only 5% to 10% of drugs entering clinical trials are proven to be safe and effective enough to enter the market, and the few programs that are successful take an average of 15 years to mature into a commercially viable drug.4 In terms of financial productivity, the average cost of developing and testing a drug prior to market entry is $1.3 billion, according to a cost analysis published on March 3, 2020 in the peer-reviewed scientific journal JAMA.32, 33

Many of these problems can be solved only through technical developments in science and engineering, but they highlight a key consideration that is often underemphasized in discussions about drug pricing: developing drugs is a risky, time-consuming, and expensive business that fails more often than it succeeds, but it can provide tremendous value to people’s lives in those instances when it does succeed. Millions of people struggle every day with health conditions for which no treatment options exist; that is, until a group of scientists, lawyers, entrepreneurs and investors venture to commercialize a treatment.

Jack Scannell, the man who coined ‘Eroom’s Law,”, commented in a 2015 Forbes op-ed that “if not for higher prices, pharmaceutical companies might never recuperate [the hundreds of millions of dollars] that are spent to generate a drug.”5 Consequently, imprecise methods of intervention, such as capping drug prices at an arbitrary threshold, might dissuade otherwise motivated individuals from even attempting to develop effective treatments, thereby leaving patients with unmet medical needs to fend for themselves. As Dr. Ge Bai — an associate professor of accounting at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School and associate professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health — notes,” We must ensure that medical innovation keeps attracting ample capital and the best talent … policies that cause capital flight or brain drain will eventually hurt every [patient in U.S. and across the world].”

It stands to reason that corrective interventions must guide the pharmaceutical industry toward behaviors that are in the financial interests of patients, while also protecting the commercial viability of the industry. In this environment, the industry can focus on what it does best: producing medicines that significantly improve the quality of life for people around the world. In the words of George Merck, the legendary president of the large pharmaceutical company Merck & Co. from 1925 to 1950, “Medicine is for people, not for profits ... when we have remembered that, the profits have always followed.”6,7 With that in mind, let’s examine how certain business leaders have managed to thread the needle between supporting the pharmaceutical industry and granting patients more affordable health care.

You Get What You Pay for, Right?

At the heart of the drug pricing issue lies a moral hazard that the U.S. health care industry is forced to confront every time a new patient receives care: What is a more vibrant body and mind worth in terms of dollars and cents? In February 2019, CEOs and senior executives of seven major pharmaceutical companies directly addressed this quandary in a public testimonial before the Senate Finance Committee.8 Pascal Soriot, CEO of the large pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, captured the attention of the ranking senators on the committee when he floated the concept of a “value-based agreement.’ Under a value-based agreement, a payment amount would increase or decrease in proportion to the benefit afforded to patients, payers and the broader health care system.

This seemingly commonplace idea is rarely considered in modern health care. When one compares treatments for different conditions, the amount patients pay for a given treatment does not necessarily correlate with its effectiveness. For example, the vaccines that have been attributed to the 1994 eradication of polio in the Americas9 can be bought by UNICEF for less than a box of Band-Aids.10 In contrast, the lifetime health care costs for the most prevalent and preventable cancers routinely exceed $100,000 but offer far greater uncertainty of a cure.11 The decoupling of price paid from value offered by a treatment regimen speaks to the seemingly endless lengths to which people will go for the chance to ensure their own well-being or that of a loved one. The lofty responsibility of ensuring that patients can be treated effectively, while also leaving their pocketbooks intact, falls squarely on the shoulders of the U.S. health care industry. In the words of Bruce Booth, partner of the life-science oriented venture capital firm Atlas Venture, “pricing ‘what the market will bear’ isn’t a viable long-term strategy […] instead, pharma needs to justify much more explicitly the pricing assumptions made using value-based principles.”4

Novel therapeutic strategies, such as cell therapies, gene therapies and immunotherapies, have the potential to dramatically alter or outright cure otherwise untreatable illnesses.12, 21, 22, 23, 24 These strategies have been adopted by various pharmaceutical companies13,29 — namely Novartis, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Spark Therapeutics, BioMarin, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Bluebird Bio — particularly for the treatment of orphan diseases, which are named as such because they correspond to niche patient populations that require special interest for drug development programs to be undertaken. Under the “pay for performance” value-based agreement established by Novartis for their spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) gene therapy Zolgensma, patients and insurers are expected to pay full price only if the drug works, or in installments over several years.14 In April 2019, AbbVie adopted an “all you can treat” value-based agreement with the Washington State Health Care Authority (HCA), in which patients pay a “subscription fee” over a predetermined time period for unlimited access to their curative hepatitis C products.29 These approaches and other value-based payment structures28 ought to be encouraged by legislators and adopted by industry leaders.

Stuck in the Middle with Whom?

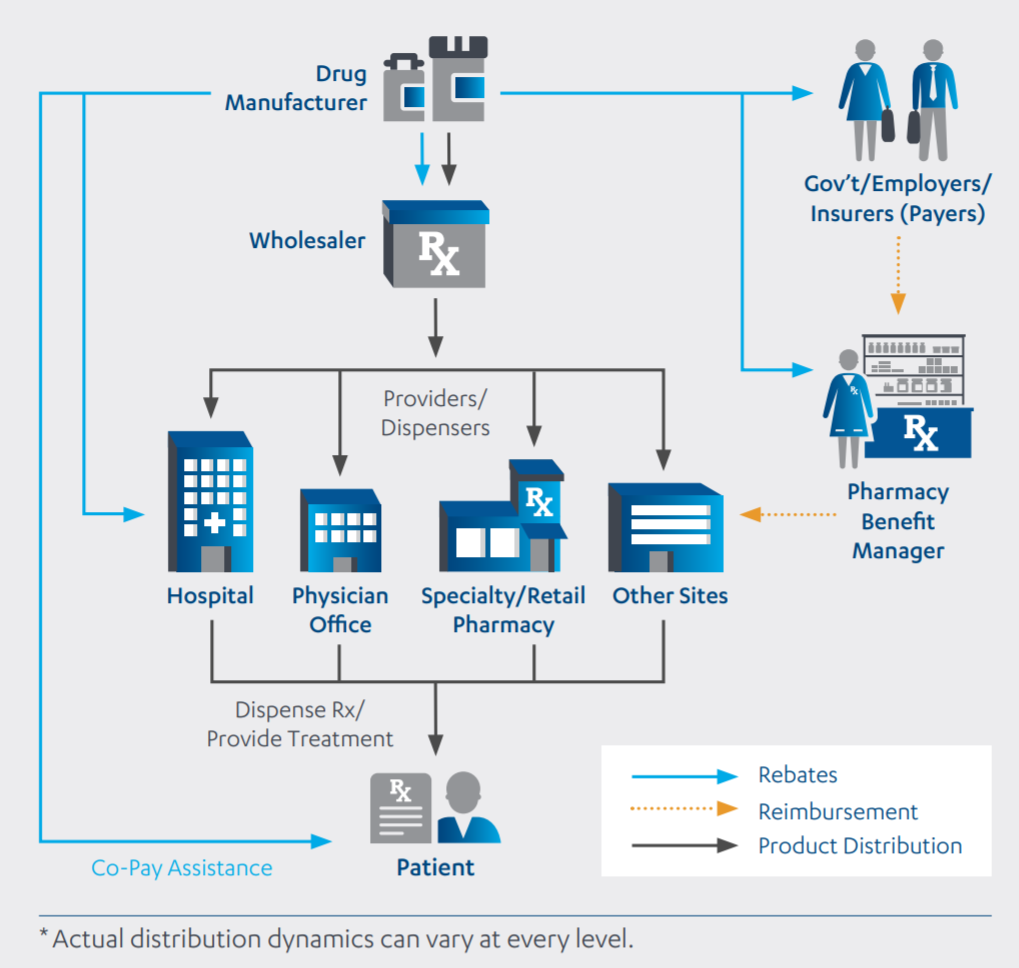

The modern pharmaceutical supply chain in the U.S. is perhaps as convoluted as it is mystifying. For a given drug to land on your bedside table, it must first make contact with a host of institutional bodies,18 which may include:

- Private Insurers (e.g., UnitedHealthcare Group, Anthem, Aetna.)

- Public insurers (e.g., Medicaid, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs)

- Pharmaceutical benefit managers (e.g., Express Scripts, CVS Health, UnitedHealth/OptumRx/Catamaran)

- Wholesalers (e.g., AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson)

- Hospitals/pharmacies (e.g., Walgreens Boots Alliance, CVS, Rite Aid)

These middlemen all pocket a percentage of the list price for a given drug — the same astronomical list prices that grace the headlines of countless editorials16 and have earned the pharmaceutical industry the most dismal reputation among the 25 business sectors that comprise the U.S. economy.17

Almost every player in this supply chain economically benefits from the further escalation of list prices. With the singular focus of expanding profits, these middlemen demand a greater proportion of the list price with every passing year. To illustrate this point, Bruce Booth cites the case of Humalog U100, an injectable insulin manufactured by Eli Lilly and taken by patients with diabetes4. From 2014 to 2018, the list price of Humalog U-100 increased by 51.2%, but the profits that accrued to Eli Lilly’s bottom line actually declined by 8.1% over that same period.19 In other words, the entire 51.2% price hike, plus an additional 8.1% of sales, flowed directly into the coffers of middlemen in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

This structure, wherein pressure stems from the middle-out, engenders a host of perverse incentives that work against the interests of the uninsured or the underinsured. It gives preferential treatment to more expensive brand name drugs, even if less expensive formulations exist. In the eyes of middlemen, higher list prices equate to higher profits, so why go through the hassle of offering generics in your hospital or pharmacy? In a 2018 Stanford Graduate School of Business talk, Ken Frazier, current CEO of Merck & Co., commented that “the current U.S. health care system is set up in a way that if you actually lowered your list price, your drug is less competitive …But if you are [a patient] paying a copay at a pharmacy, you would prefer a lower list price … We ran an experiment with Hepatitis C to see what would happen if we brought a drug to market at a lower price than our competitors … A lot of actors in the [U.S. health care] system disfavored a product with a lower list price and there’s something wrong with that.”20 The inflationary pressures brought about by middlemen forces pharmaceutical companies to inflate their list prices, else they risk market suppression of their drug.

So, who in their right mind has the intestinal fortitude and economic wherewithal to challenge the powerful, multibillion-dollar industries that embody the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain? The answer: the other powerful, multibillion-dollar industries that embody the U.S. financial services and technology sectors. In January2018, Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of the investment bank JPMorgan Chase; Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of the multinational holding company Berkshire Hathaway; and Jeff Bezos, president and CEO of the e-commerce and cloud computing company Amazon co-announced a joint venture called Haven,25 a company aimed at lowering health care costs for their employees. Traditionally, pharmaceutical companies are forced to negotiate with middlemen incumbents, who act as gatekeepers for market access to the hundreds of millions of American consumers. Similarly, Haven will negotiate on behalf of the hundreds of thousands of employees it represents, but its unique status as a not-for-profit entity removes the middle-out inflationary pressures that plague the rest of the health care system.

In other words, Haven’s business model is more amenable to favoring lower-priced alternatives over higher-priced brand name drugs. Additionally, Haven won’t drive up list prices for drugs — as was the case for Humalog U-100 — because its nonprofit operational structure doesn’t demand an ever-growing proportion of its sales. Though specific details of the venture remain under wraps, Dimon, Buffett and Bezos envision Haven as being piloted by employees in their representative companies and eventually scaled up to be incorporated into employee health care packages offered at other companies.26 Nevertheless, Haven should serve as a signpost for the herculean efforts that are being undertaken to fundamentally change the U.S. pharmaceutical landscape.

Concluding Remarks

Every year, the “who’s who” in the global health care and investment industries convene at the JPMorgan Healthcare Conference. On January 8, 2020, the conference began with a New Year’s resolution of sorts — a “New Commitment to Patients,” signed by more than 300 pharmaceutical leaders.27 It outlines a promise, on behalf of the industry, to reorient U.S. health care around maximizing ethical standards and ensuring that drugs remain financially accessible to patients who need them. Our responsibility as Americans should be to hold the industry accountable for these promises and ensure that corrective interventions also allow life-changing innovations to thrive.

Your voice on this matter can readily translate into tangible results if you alert your state representatives to take action on your behalf. The introduction of AbbVie’s “all you can treat” value-based payment structure, which aimed to improve financial access to its hepatitis C drugs, was galvanized by Governor Jay Inslee’s goal of eliminating hepatitis C in the state of Washington by 2030.29 Interested parties are encouraged to contact their state legislators (Senate,30 House of Representatives31 ) and urge for interventions, such as those established by Governor Inslee. Meanwhile, patients and their families should gain a renewed sense of confidence from knowing that both establishment pharmaceutical companies and large companies in other private sectors of the U.S. economy are united in their efforts to deliver more affordable drug prices by introducing disruptive business models. We as individuals, students, employees and even the companies where we work are all stakeholders in the U.S. health care system. It is in our collective interests for the system to take a more patient-centric approach to guarantee our ability to attain the highest quality of life.

References

- https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/history/index.html

- https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/museum-gordon-moore-law.html

- Scannell, J.W., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H. and Warrington, B., 2012. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 11(3), p.191.

- https://lifescivc.com/2019/12/venturing-a-perspective-on-the-drug-pricing-debate/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherper/2015/10/13/four-reasons-drugs-are-expensive-of-which-two-are-false/

- https://www.merck.com/about/our-people/george-merck.html

- https://www.merck.com/about/our-people/gw-merck-doc.pdf

- https://www.c-span.org/video/?458198-1/lawmakers-press-pharma-ceos-rising-drug-prices

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00032760.htm

- https://www.unicef.org/supply/files/OPV_prices_25072019.pdf

- https://www.asbestos.com/featured-stories/high-cost-of-cancer-treatment/

- https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2020/01/genome-engineering-emerges-from-the-shadows/

- https://www.statnews.com/2019/04/08/value-based-therapies/

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/novartis-ceo-narasimhan-preps-zolgensma-launch-call-for-new-drug-payment-model

- https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/28/insulin-pricing-becomes-top-issue-for-democrats/

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/novartis-to-offer-worlds-most-expensive-drug-for-free-via-lottery-11576767894

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/pharma-sinks-to-new-low-annual-gallup-ranking-puts-industry-dead-last-consumer-regard

- https://jnj-janssen.brightspotcdn.com/b9/96/70c52ba14482a97c48bdfebf0471/2017-janssen-us-transparency-report-march2018.PDF

- https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-0hrQ7JC5sIM/XJu1TTgEogI/AAAAAAAAbDY/wUBTJ_MtewI3L45xwdJOnoR3dhYjOvgAgCLcBGAs/s640/LYY-Humalog.PNG

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytU0Re2QVoI&feature=youtu.be&t=852

- https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2018/07/landmark-rnai-based-therapy-achieves-clinical-success/

- https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2019/02/engineering-magic-bullets-for-pancreatic-cancer/

- https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2018/03/a-novel-cancer-immunotherapy-unveiled-y-traps/

- https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2018/10/solving-the-car-t-conundrum/

- https://www.statnews.com/2018/01/30/amazon-jpmorgan-berkshire-health-care/

- https://www.statnews.com/2019/06/05/haven-broader-vision-dimon/

- https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/08/new-biotechnology-pharmaceutical-industry-commitment-patients-public/

- https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/health-research-institute/assets/pwc-2019-us-health-drug-pricing-digital.pdf

- https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/hca-finalizes-contract-abbvie-eliminate-hcv-washington-state

- https://www.senate.gov/general/contact_information/senators_cfm.cfm?OrderBy=state&Sort=ASC&fbclid=IwAR2hrVaKh0PEudaX8SqZsizgU_sv4lkL8jHkETlvr_DIjiyDdnxkegL2Mew

- https://www.house.gov/representatives/find-your-representative?fbclid=IwAR1SCbymMvdzlQUfsN0LQ5PEdszybr43f2uLnm2vP85G5xDc2Yho5mtHM5U

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2762311

- https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2020/03/03/drug-development-billions-cost/

Related content

- A Life or Debt Decision: Tackling Unaffordable Drug Prices in Maryland

- From Books to Business: A Hopkins Student Experiences the Biopharma Industry Firsthand

- The Rising Cost of Pharmaceuticals

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.