Please note: This article was written before the coronavirus pandemic, and therefore prior to any protocols or mandates around physical distancing and masking.

“Find a work of art that inspires you,” my prompt read.

Making my way through the Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art, I kept my eyes peeled for a portrait or sculpture that evoked such a feeling. I was joined by my peers — first- and second-year medical students at Johns Hopkins — each of whom had their own preselected objectives: “Find an object that, for you, embodies pure joy,” “Find an image of a person you would like to meet,” and so on.

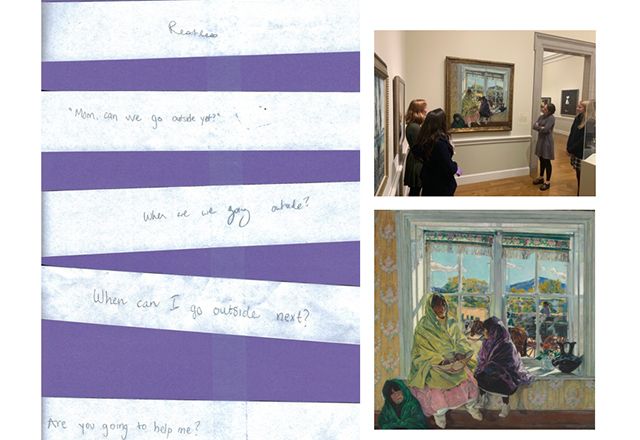

I settled on a dusky-yellow painting called Interior on a Grey Day, Vaucresson (1921–22) by the French artist Edouard Vuillard. The piece portrayed an elderly woman in her home, holding a piece of garment above her bed. She was alone, and the subdued colors of the distemper instilled a rather dreary, ruminative tenor to the scene. I wondered how this piece, out of the many other more glamorous and evocative exhibits in the collection, captured my attention. I quickly realized it was because the woman reminded me of my mother — modest and unassuming, but robust in her character, dignity, diligence and love for family. The static work of art did little to communicate these features, yet its invitation to personal interpretation and application — characteristic generally of art — led me to think about the inspiration of my mother. Only after I shared my reflections with my group did I read the exhibit label: “…This intimate interior depicts Vuillard’s mother … he captures her with grace and dignity in a still and contemplative moment.”

The students in our group, led by Margaret “Meg” Chisolm and Susan Lehmann, faculty psychiatrists at the school of medicine, were participating in an art museum-based educational experience called the Personal Responses Tour.1-2 Developed by Ray Williams (now director of education at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas) in the 1990s, the Personal Responses Tour is a reflection exercise that employs images in art museums as reflective triggers to “provide learners with a safe and effective avenue to approach issues of meaning, explore sensitive or ‘taboo’ topics, or discuss complex emotional responses.”2 Participants randomly select a prompt intended to invite an emotional response to some meaningful aspect of human life. They are asked to identify and spend some time with a work of art that resonates with them in light of the prompt, and then to share their reflections with the group. Through this process of exploration and contemplation, learners have the opportunity to engage their curiosities, hone their observational skills and deepen their self-understanding. Empathic listening also creates a sense of closeness as participants learn more about each other’s experiences and internal worlds.

Our time in the museum began that day with an activity using a student-centered teaching approach called Visual Thinking Strategies.3 In this approach, learners gather to carefully and deliberately scrutinize a single work of art complex and ambiguous enough to sufficiently permit thoughtful analysis and discussion among the learners. We were led by Dr. Chisolm to a large painting, Rinaldo and Armida (1629) by the Flemish artist Sir Anthony Van Dyck, and given several minutes to look at the piece. Dr. Chisolm then initiated a discussion among our group by asking, “What’s going on in this picture?” Taking turns, many of us voiced our independent insights about the diverse features captured in the piece — what we noticed, what we thought it meant, what we were confused by. The discussion continued with a series of two other thought-provoking questions: “What do you see that makes you say that?” (intended to help us ground our observations in evidence) and “What more can we find?” (to add nuance to our conversation and encourage deeper looking). I was excited and impressed by how much we extracted out of a single work of art simply by taking the time to notice. Moreover, I appreciated the value of the exercise in fostering my awareness and understanding of different perspectives — namely, those of my peers, whose observations and interpretations I may have never come to on my own. Regarding this facet of Visual Thinking Strategies, one research team remarks, “[Participants] develop insights about their biases… as group members become aware that everyone has a unique perspective, we see that the group increasingly appreciates multiple perspectives, tolerates uncertainty, and works as a team.”3

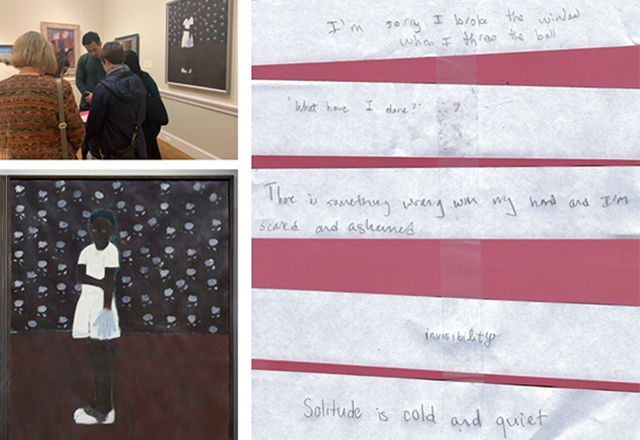

Following the Visual Thinking Strategies exercise, we were evenly divided into two groups for our next activity. Each group was given a painting to observe. While half the students spent time with Luzanna and Her Sisters (1920) by the American artist Walter Ufer, my group and I studied an untitled piece depicting Boy with Blue Hand (1982) by the American artist Kerry James Marshall. Each of us was asked to write down on a strip of paper what we thought the subject in the piece might be thinking or saying. We then had to arrange each of our lines sequentially to produce a poem about the piece, which we recited to our peers in the other group (and they for us). Critical thinking, teamwork and, most importantly, empathy — putting ourselves in the minds and positions of our subject and considering what they might be experiencing — were all emphasized in this creative activity.

The Personal Responses Tour came next, during which I found the painting that so strongly evoked thoughts of my mother. After that, our museum experience concluded with a contemplative individual activity called “And I noticed…” We were each given an index card on which we were to write any observations or thoughts we had as we strolled through and examined the vast array of sculptures, pottery and other objects in the Asian and African art galleries. This was intended to promote introspection and open-ended self-reflection both about the new art we were seeing and about the entirety of the afternoon we experienced together. We gathered together and shared what we noticed — about the art and about ourselves.

Why should we use art museums in medical education? By the end of our visit to the Baltimore Museum of Art, it was evident to me how our activities helped cultivate certain skills and qualities essential not only to my future practice as a clinician but also to my life now as a student and person. I was pleased to find within the academic literature support for arts-based education as an effective modality for nurturing the personal and professional lives of current and aspiring health care professionals. Studies (summarized in [3]) have shown that arts-based education may improve identification of diagnostic features on radiography, tolerance of ambiguity, reflective ability, awareness of biases, empathy, emotional recognition and connections with patients — all of which have clear implications for me at this juncture of my medical education, when I am learning how to become an effective and patient-centered clinician. Although there is a scarcity of published research on arts-based education among non-medical graduate students, I believe the opportunity to cultivate such important intra- and interpersonal skills would be a welcome contribution to these students as well.

On a personal level, arts-based education may also help health care workers deal more effectively with burnout.4 One way in which this might happen is by providing individuals with the opportunity to process their feelings in displacement — that is, a work of art provides an external haven to which individuals can shift should their revelations become too personal. “[Art] serves an important modulating function to simultaneously achieve depth of discussion and emotional safety,” write Ray Williams and Elizabeth Gaufberg of Harvard Medical School. “The physical separation from the stressful hospital environment within a peaceful, controlled museum environment seems to foster renewal and may complement efforts to prevent burnout.”2 Indeed, a systematic review and meta-synthesis of the use of arts in medical education found important benefits in emotional processing for medical students, “who are often taught that illness is a problem to be solved through objective means, denying the emotional experience of professional practice.”5

The review also summarized some unique qualities of the arts that promote personal and professional growth among medical learners. For instance, the ambiguities, complexities and subjectivities inherent in most works of art enables learners to become better at exploring, managing and being unafraid of these tensions when they arise in clinical practice. Moreover, the dual universality and foreignness of the arts tends to help learners engage with one another on a level playing field; regardless of their professional status or rank, no one is an expert when confronted with culturally unfamiliar works of art. This opens “new cross-cultural conversational doors” and paves the way for mutually edifying learning, which is crucial in helping learners better understand new or diverging perspectives; indeed, arts-based workshops enable learners “to reach beyond the safe boundaries of the familiar to hear and see the experiences of others.”5 The importance of empathy in the medical profession, and the way in which arts-based learning can help hone this attribute, cannot be overstated. Other skills found to be enhanced through art among medical learners include “observation, communication, critical thinking, ethical reasoning and the ability to think creatively.”5

At Johns Hopkins, Meg Chisolm spearheads the effort to implement art museum-based learning within all levels of medical education. Besides leading reflective museum sessions for medical students, Dr. Chisolm is supported by a Johns Hopkins Ten by Twenty Challenge grant to run these sessions with a focus on professional identity development for pre-health students at Johns Hopkins, as well as a grant from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Excellence in Education — with principal investigator Kamna Balhara — to develop a continuing medical education course for Hopkins faculty and other practicing physicians. Furthermore, Dr. Chisolm is piloting a four-week art museum-based elective for medical students, which is proposed to be available to fourth-year students beginning February 2021.

Not a usual visitor of museums, I valued seeing how art gave me the special opportunity to connect more deeply with myself and my peers. I left the Baltimore Museum of Art feeling renewed. Appreciating the beauties and complexities of what it means to be human and reflecting on what it means to lead a good life, I was offered an enjoyable and nurturing space to ponder the questions that drew me to medicine in the first place. Ray Williams describes the Personal Responses Tour as “‘a strategy for serving the public hunger for connection’… works of art are seen to matter as manifestations of human experience, aspirations and wisdom. Members of a group come to know one another better during a ‘Personal Response’ tour — learning how they might offer support to a friend or colleague, gathering the seeds of future conversations.”

“All it takes is the invitation — and a sense of safety.”1

For more information about art museum-based initiatives at Johns Hopkins, contact Meg Chisolm at [email protected] or visit closler.org/contributors/margaret-chisolm.

Sources

- Williams, R. (2010). Honoring the Personal Response. Journal of Museum Education, 35(1), 93–102. doi: 10.1080/10598650.2010.11510653

- Gaufberg, E., & Williams, R. (2011). Reflection in a Museum Setting: The Personal Responses Tour. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 3(4), 546–549. doi: 10.4300/jgme-d-11-00036.1

- Zarrabi, A. J., Morrison, L. J., Reville, B. A., Hauser, J. M., Desandre, P., Joselow, M., … Wood, G. (2020). Museum-Based Education: A Novel Educational Approach for Hospice and Palliative Medicine Training Programs. Journal of Palliative Medicine. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0476

- Orr, A. R., Moghbeli, N., Swain, A., Bassett, B., Niepold, S., Rizzo, A., & Delisser, H. M. (2019). The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, Volume 10, 361–369. doi: 10.2147/amep.s194575

- Haidet, P., Jarecke, J., Adams, N. E., Stuckey, H. L., Green, M. J., Shapiro, D., … Wolpaw, D. R. (2016). A guiding framework to maximise the power of the arts in medical education: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Medical Education, 50(3), 320–331. doi: 10.1111/medu.12925

Related content

- Hospital Buildings: An Under-Appreciated Art (and Science)

- Put a Little LOVE in Your Art: Murals of Baltimore

- Art As Applied to Medicine: the 2019 Graduate Showcase

Want to read more from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine? Subscribe to the Biomedical Odyssey blog and receive new posts directly in your inbox.

Local art museums, with sessions led primarily by art educators employing validated pedagogy such as Visual Thinking Strategies or Artful Thinking. Very helpful for medical students.

Comments are closed.