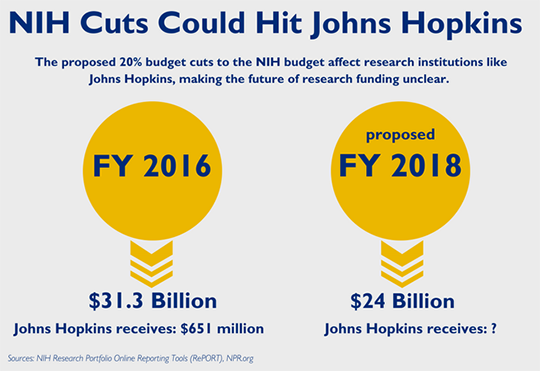

Potential Cuts to Science Funding Threaten US Position as World Leader in Biomedical Research

We Americans are privileged to live in a country that boasts the top scientific research in the world being conducted in our laboratories, research institutions… Read More »Potential Cuts to Science Funding Threaten US Position as World Leader in Biomedical Research